Revolution and Remembrance in Bristol

Were there to be an award for most patriotic town in America, Bristol, Rhode Island could compete fiercely. The town’s claim to fame is that it is home to the oldest continuous Fourth of July celebration in the nation. What began in 1785 as a simple sermon and a thirteen cannon salute has now morphed into a two-week long celebration that regularly attracts six-figure crowds of out-of-towners. Beyond the obvious growth of the ceremony, the character of the Bristol tradition has also evolved over its 236 years. Through every historical development, the nation has continued to try to define itself, a mission that quickly proves futile if one seeks a singular answer. Any historical commemoration has to grapple with both the past and the present in considering how its manner of remembrace reflects both the position of contemporary society and an accurate interpretation of the past. Coming from a historical moment that feels particularly polarized in the fight over patriotism and national heritage, this tour seeks to take a reflective approach to the changes in a nation’s self-conception. It is concerned primarily with the local, and makes no attempt to be exhaustive in its treatment of the revolution and its enduring successes and failures. Histourian’s format continues to evolve: in this instance specific sites are identified and described as ancillary material to the main narrative, which again encourages a peripatetic and observant walk around town.

1. Independence Park (419–459 Thames Street)

It is entirely possible that one would have been able to see the burning of the Gaspee from the point on Bristol harbor that is now Independence Park. Across Narragansett Bay and a narrow neck of the Poppasquash peninsula, Gaspee Point is seven miles northwest, as the crow flies. Bristol Harbor, which dominates the foreground of this view, would have been busy with ships of all types at this time. The town was a major hub of maritime activity from fishing, to shipbuilding, to international trade.

As with many colonial towns, especially in Rhode Island, activity was drawn toward the bustling harbor. A particularly consequential day in the history of Bristol’s harbor was October 7th, 1775, when a fleet of British ships dropped anchor. According to the description from local historian W. H. Munro, upon their arrival, “the greater part of the population, suspecting no evil, assembled upon the wharves to gaze upon the unusual spectacle. Never had the harbor of the old town beheld a more striking display than was then presented. With sails that were only just distended by the dying breezes, the ships drifted slowly over the water that rippled with gentle murmurings about their bows. The rays of the setting sun tinged every mast, and sail, and rope with a golden light, making a scene of wondrous beauty, that never faded from the recollection of those who beheld it. Everything seemed to speak of peace, except the black mouths of the frowning cannons that here and there lurked, as if forgotten, in the dark hulls of the larger ships.”

Even the most casual student of the American Revolution is familiar with the ways in which the colonists resisted the encroaching arm of the British empire in the years leading up to the Revolution. Americans began seeking to delimit and defend both their economy and their political culture as separate from imperial Britain in the decades before official Independence was declared or war broke out. Through the regulatory measures of the Navigation Acts, Britain favored its own ships, goods, and interests, which—perhaps more on a matter of principle or perceived cost than of actual demonstrated detriment—offended the American colonists and pushed them toward rebellion.

British ships regularly searched American cargo ships and seized wares in an effort to enforce the Navigation Acts. Colonists felt that this supplanted the authority of their governors, a rage which emboldened them to resist. When the HMS Gaspee, deployed on an enforcement operation in Newport harbor, ran aground chasing the packet ship Hannah up to Providence, patriots seized the opportunity to besiege the ship. Some have called the Gaspee Affair, June 1772, the first blood shed during the Revolution, and lament that it is a lesser known protest than the Boston Tea Party which took place the following year.

When the Gaspee ran aground by Namquit point in Warwick on June 9, 1772, word spread quickly through the neighboring towns. Providence patriots took out eight boats and, joined by one from Bristol, boarded the stalled vessel just before dawn on June 10. Led by John Brown of Providence and Simeon Potter of Bristol, the insurgents captured the crew and set the boat on fire. Word of this conspicuous attack spread like fire throughout the colonies, but England was unsuccessful in prosecuting any suspects due to protective testimony from fellow townspeople.

The man who led Bristol’s contribution to the Gaspee Affair, Simeon Potter, was not formally educated but was a staunch believer in the principles guiding the burgeoning fight for American independence. He was raised on the sea and maintained the rugged and adventurous spirit that to many Americans typifies a patriot. A poem written down by Potter (and also recounted elsewhere) exemplifies this attitude:

2. Bosworth House (814 Hope Street)

This house, built 1680 was one of the first structures erected in colonial Bristol, and is currently the oldest surviving home in the town. It served both religious and schoolhouse purposes before separate buildings were completed for those functions. It was one of few buildings to be struck by the English bombardment of 1775, along with a church steeple. It is said that cannonballs were discovered lodged between the two stories during later renovations. Built by Deacon Nathaniel Bosworth, situated on Silver Creek, later occupied by the prominent Perry family, and finally converted to apartments by Regos, this historic home goes by many names.

Such patriotic spirits pervaded the colony of Rhode Island and the town of Bristol during the era of the Revolutionary War. As early as February of 1774—the same month Parliament officially declared Massachusetts a rebellious colony—Bristolians were in correspondence with Bostonians over the coordination of resistance forces. On May 4, 1776, Rhode Island formally declared independence from England, exactly two months before the Continental Congress would do so on behalf of all the North American colonies. Later, when the state took its first vote on the adoption of the federal Constitution in 1788, Bristol was one of only two towns (joined by Little Compton) to vote in favor. Rhode Island eventually became the last state to ratify the Constitution in 1790. By that time, Bristol had already been celebrating the anniversary of the nation’s independence for five years.

Bristol has more reason to celebrate this holiday so ardently than the general patriotic inclinations of its historic population. Two combative events occurred during the Revolutionary War on Bristol soil that give the town greater stake in its legacy. The first was on October 7, 1775, when three British warships anchored in Bristol harbor, accompanied by a fleet of smaller vessels. The ships Rose, Glasgow, and Swan sailed up from British-occupied Newport under the command of Captain Sir James Wallace, who demanded local representatives come aboard his ship for a meeting. Governor Bradford responded by saying that Wallace could come to the wharf if he really wanted to speak with them. In response to this call, the frigates began firing their cannons at the town. After an hour and a half of continuous bombardment, Simeon Potter boarded the Rose to call for a pause in the assault while the town assembled a committee to meet with Captain Wallace. Wallace’s business was to demand rations for his troops—on the order of 200 sheep, which the Bristolians negotiated down to 40. Even after the British received this payment, they plundered additional livestock and fired shots on their way out of town. The fact that most cannon shots passed directly over town and landed on farmland, leads historians to believe that “it seems probable that the object of Wallace was not to harm the town but only to intimidate its inhabitants.” Few buildings were damaged and the only person to die was Parson Burt who suffered from heart attack symptoms while hiding out in a field during the attack.

3. Reynolds House (956 Hope Street)

As the Hessian soliders marched south during the invasion, they took the inhabitants of several homes captive. Most members of the Reynolds household were able to escape in advance, except Mr. Samuel Reynolds who was brought to Newport briefly as a prisoner. Lafayette also used this house as a base of operations during September 1778, for which it is memorialized as a National Historic Landmark.

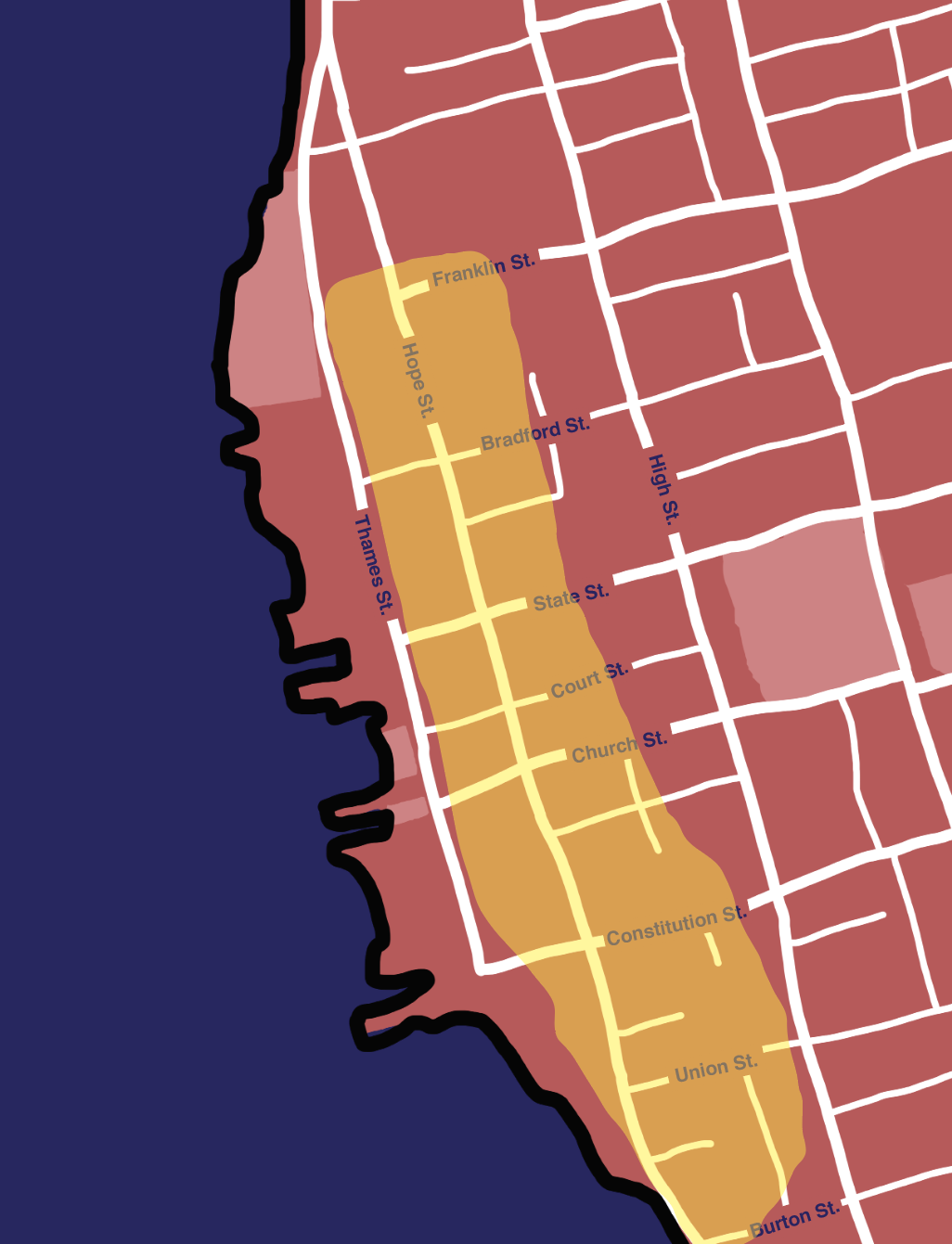

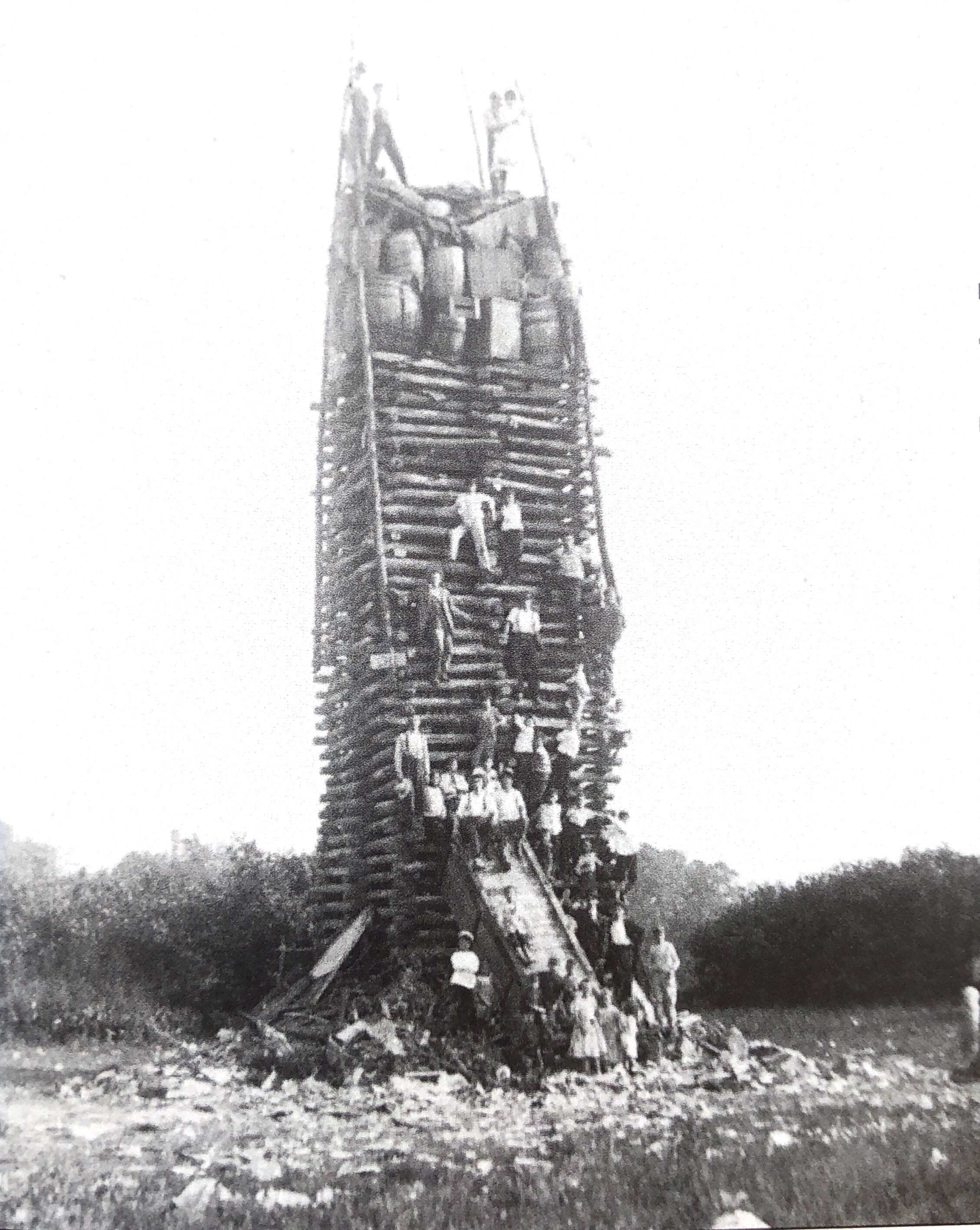

The second conflict on Bristol soil, which left a much greater physical scar on the town, was the invasion and burning by Hessian soldiers on May 25, 1778. Five hundred troops led by British Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell landed on the west side of town and marched north to Warren to destroy an idle American fleet on the Kickemuit River. They did not stop at burning the ships, but succeeded in torching and plundering a significant part of town before retreating. The thickly settled area of town was almost entirely engulfed in flames, explaining why so many of the oldest homes that give Bristol its historical charm today are from the 1790s onward. The scope of the fire is roughly outlined on the map below. Hope Street was the main thoroughfare at this time, as now.

Only two years after the Treaty of Paris, and nine years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Bristol had its first documented Fourth of July celebration composed of a sermon, cannon salute, and widespread sense of revelry. In these early years, the occasion was affected by more of a sense of urgency, relief, and military victory than what is now taken to be a holiday of civic and national pride. The rest of this tour concerns precisely this transformation in the manner of remembrance of the Fourth of July.

4. Bradford-Dimond-Norris House

(474 Hope Street)

Though the route has not been the same throughout the Bristol parade’s history, it often commenced at a hotel, where the crowd would gather and begin the procession through the streets. Horton’s Hotel on State Street was a longtime fixture of the parade, and in the temperance years Burgess Temperance Hotel was favored. Neither of these structures still stands. Now, the Bradford-Dimond-Norris House is one of the most historic hotels in town, constructed in 1792 for Rhode Island politician William Bradford after his previous home was destroyed in the Revolutionary War.

Information regarding the town’s celebrations in the early decades of nationhood is somewhat spotty. It seems that the tradition came together in a rather piecemeal and organic fashion—what began as a sermon and salute soon expanded into a procession, and eventually became standardized as a parade. Defining features of early celebrations were noisemaking and revelry. Local historian Richard Simpson explained that early parades “would certainly not be the same without the cacophonous booming and banging of pyrotechnics, firearms, and other noisemakers. This racket-making often kicked off the celebrations.” Townspeople, many of whom had fought in the Revolutionary War or at least known someone who had, marked the holiday as one of relief and acute military victory; what we have long understood as institutionalized American rights were not yet taken for granted. This more urgent tone of early celebrations persisted through the War of 1812, after which the ship Yankee returned to Bristol harbor for a celebration in which “everything smelled of powder and patriotism, and breathed the downfall of England.”

By the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, enough momentum had accumulated around the annual celebration to make it an anticipated event. Simpson gives the following description of the 1826 parade: “The Bristol Train of Artillery fired the cannon at sunrise and church bells were rung. Young Americans were up bright and early with firecrackers, small cannons, tooting horns, and conch shells. By nine o’clock, the streets were crowded to witness the procession, forming in front of the Court House on High Street at 10 o’clock.” This was likely one of the last celebrations to feature actual veterans of the Revolutionary War—twenty-seven of them were participants in the patriotic exercises.

5. First Congregational Church (281 High Street)

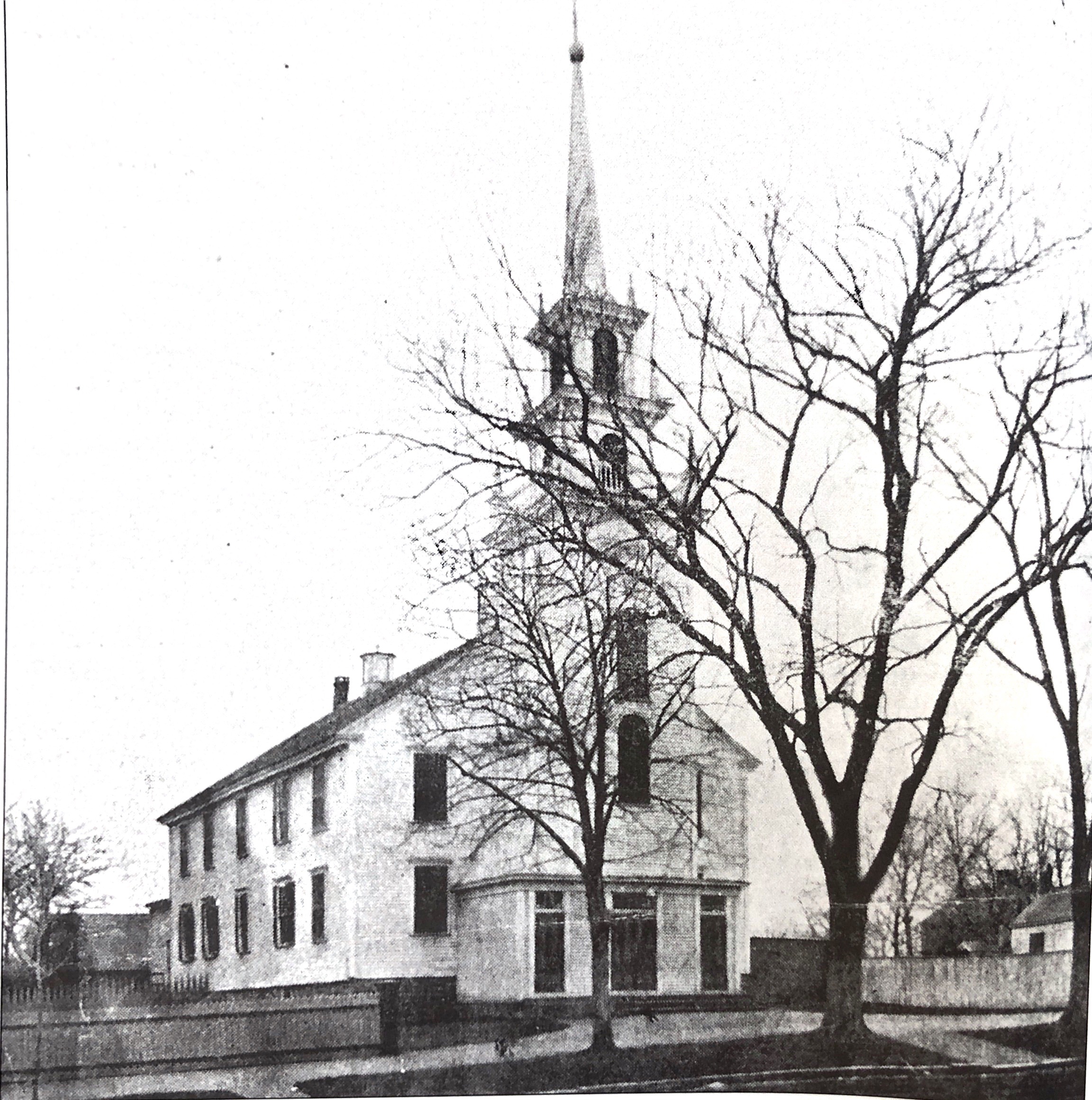

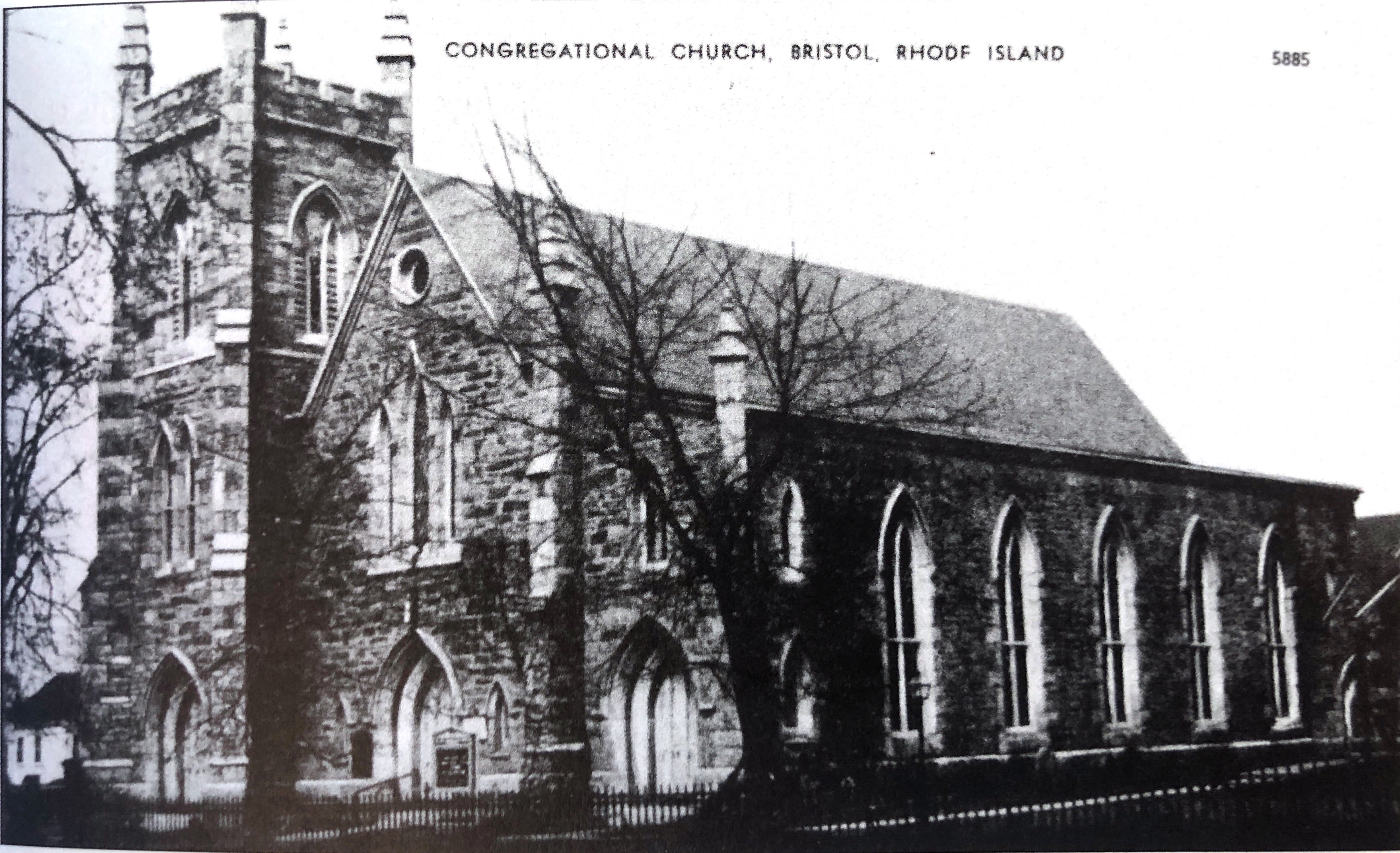

The parade has often terminated at First Congregational Church, which has occupied three different buildings since it first gathered, built in 1683, 1784, and 1856. The first burned down in a fire, the second became town hall and was then razed, and the third stands today. The Congregational Church has a long history as a leader in the social and political life of New England towns and was one of the most influential institutions in forming the sensibility of the region in the colonial and early national years. The Reverend Henry Wight, who himself was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, established in 1785 the tradition of a sermon at Bristol’s Patriotic Exercises and continued to deliver the tradition until even after he retired from the church.

While these early celebrations were some of the most raucous, they were also among the most pious. Congregational minister Henry Wight gave the first Independence Day sermon in 1785 and continued to do so until his death in 1838. In this 1836 year he professed: “We rejoice and thank God on this joyous anniversary, that we may assemble in a temple dedicated to His service, and offer homage of our grateful hearts for His deliverance vouchsafed to our Fathers when the storms of war lowered upon their destinies; and their blood-nurtured battalions of a sanguinary Despot swarmed upon their shores.”

In the following years, the parade grew increasingly austere, especially as temperance organizations took over the administration of the affair. The rising temperance movement of the early nineteenth century was motivated by a combination of righteousness drawn from the nation’s founders, sentimentalism of the Romantic era, and moralistic fervor of the second Great Awakening. During the Second Great Awakening, personal accountability and resistance to temptation were center stage among Protestants who feared the excesses brought by Catholic immigration. They “became alarmed over the growing incidence of public drunkenness in the state, especially on holidays like the Fourth of July.” In their eyes, the burden put on the government and the general public to accommodate drunkards was inordinately high. Taverns were central to social life (and to political life as well, see: NYC as Capital tour), clean water was hard to come by, and the trade of spirits was a lucrative exchange with Britain, all of which contributed to the centrality of alcohol in public life. Between the Revolution and 1828, per capita alcohol consumption was at the highest level it has ever been in the country’s history.

6. Town Common

The town common is the location of numerous civic-minded recreational Fourth of July activities. In the late nineteenth century baseball games were the main attraction, a tradition that lives on in today’s “vintage baseball game.” In 1897, in a lighthearted celebration of technology and innovation “an illuminated bicycle parade was held around the Common. Three prize medals were offered by the committee for the best illuminated and decorated wheels.” Today the carnival is the common’s main attraction in the lead-up to July Fourth.

Temperance organizations rose rapidly in the 1830s, with organizations like the Young Men’s Temperance Union, Sons of Temperance, Bristol Total Abstinence Society, and Cold Water Army all active within the town. The local manufacture of rum, which had been a significant business for Bristol in the colonial and founding eras, ceased entirely by the 1830s. Temperance organizations took charge of the Independence Day celebrations which had previously been an occasion for revelry, merrymaking, and even debauchery. Exemplifying the impacts of the temperance movement on local attitudes, the Bristol Gazette reported of the 1834 parade that “Friday the Fourth of July, was celebrated in this town with more spirit and animation than we ever before witnessed. A great number of the citizens of neighboring towns and villages participated in the festivities of the occasion, and we are sorry to say that some of these visitors did not behave themselves as well as they should have done.” Temperance organizations did more than police the behavior of celebrants: they reframed the conversation around patriotism and national identity to make it fit within the context of their movement.

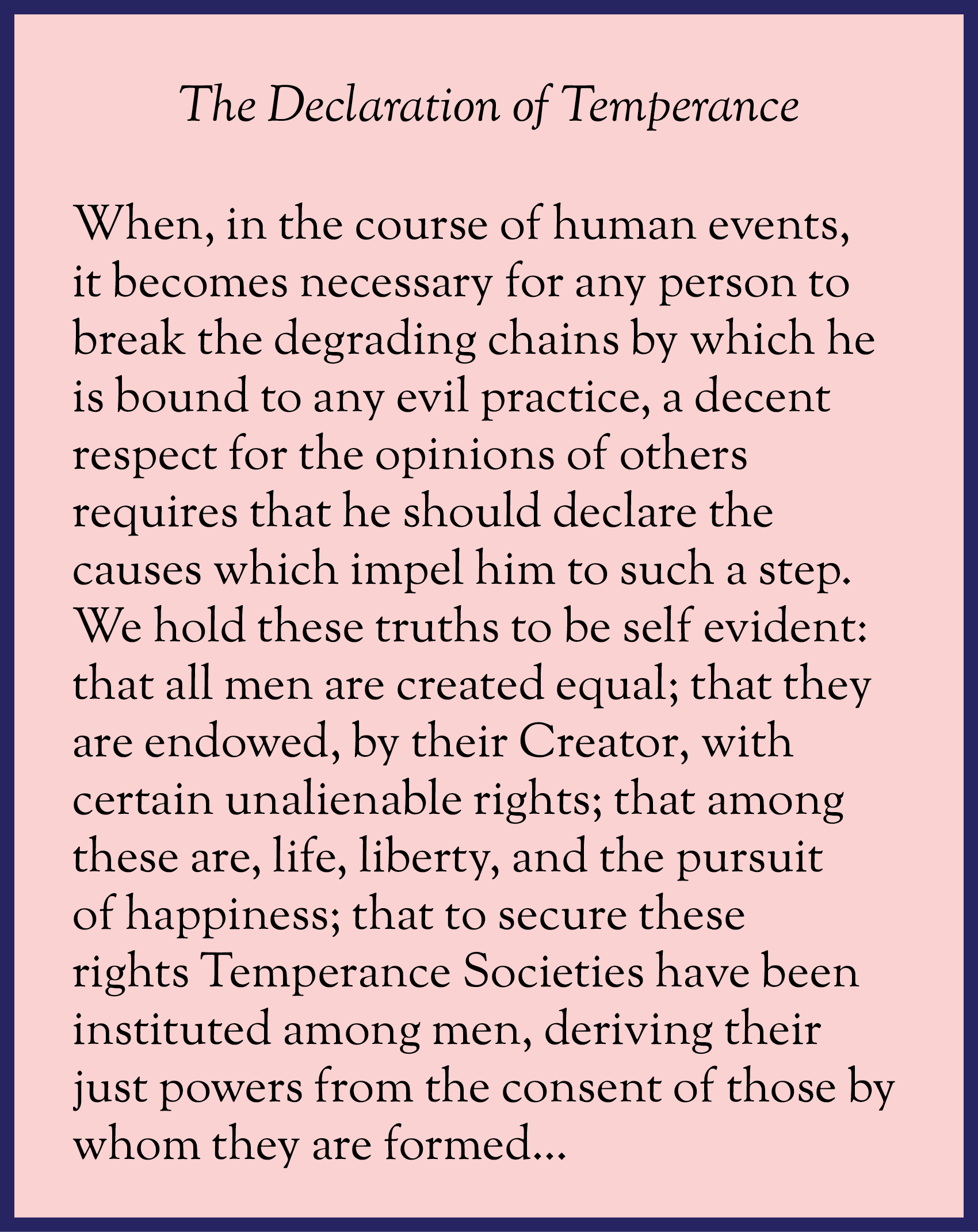

Reciprocally, they organized the articulation of their own movement around the language of national independence to further affiliate the two causes. In 1833, the Rhode Island Temperance Advocate wrote in a circular addressed to the young men of the state: War is over “but an enemy more grasping, more despotic, more deadly, is still entrenched within our borders. Instead of hovering about our coasts, and now and then laying waste a defenceless town or village, this enemy has penetrated every corner of our Country, violated ten thousand altars of domestic peace, and desecrated the sanctuaries of our God. It would wrest from us, not only our fortunes, our liberty, our honor, but our reason, our happiness, our lives. It has long been feeding on the spoils of ruined homes and broken hearts—yet its appetite is still ungorged. Our fathers, brothers, and friends have fallen victims to its rapacity, and the tears of wives, children, and orphans call upon us, by all that is endearing in the ties of social compact, speedily to avenge their wrongs. This enemy is Intemperance. Young men of Rhode-Island! we have united to make war upon this enemy. Can you not, will you not help us? Friends of your Country and of humanity! we earnestly and affectionately invite you to engage in the noble work of achieving our second Independence.” This very direct framing of the temperance movement in the image of the founders continues even more explicitly in the “Declaration of Temperance’’ printed in the same circular that mirrors almost exactly the language of the Declaration of Independence.

Temperance societies had a grip on the Bristol parade throughout most of the 1840s. By 1843, average alcohol consumption per capita in the nation at large was down to just 20% of its 1828 peak. The 1848 celebration was the last to be officially run by temperance organizations and it was reported that “the procession was the largest yet seen.” Even after the official administration of the celebration returned to a municipal committee, the commentary of the temperance movement lingered. In 1851, an op-ed in the Bristol Phoenix wrote “It is our earnest wish and we doubt not, the earnest wish of all good citizens that the day may pass off without noise, or dissipation of any kind, in an orderly and quiet manner,” a significant departure from the raucousness that had been lauded in the same paper in recent memory.

By the end of the nineteenth century—as the nation recovered from the Civil War, long-distance communications technology evolved, and opportunities for leisure expanded—a new national identity began to emerge. The Bristol parade expressed this civic pride through its emphasis on recreational activities that skirted the contentious topics of religion and politics. Baseball games and bicycle races became some of the celebration’s most fashionable events—both having recently emerged as popular pastimes across the country. From the 1880s onward, coverage of the celebration in the Bristol Phoenix focused more on the revelry than on the preaching, perhaps signifying a swing away from the piousness marked by the temperance era. In 1890, one celebrant commented: “If tin horns and firecrackers are sure proof of patriotism, then our town is one of the most patriotic in the country—for during the 4th there was more noise to the square inch from these agencies than is often experienced anywhere.”

7. Town Hall (10 Court Street)

The parade receives partial funding from the town, the rest being raised in events. This creates a complex relationship between the two interdependent organizations working to sustain the town’s economy and tourist appeal.

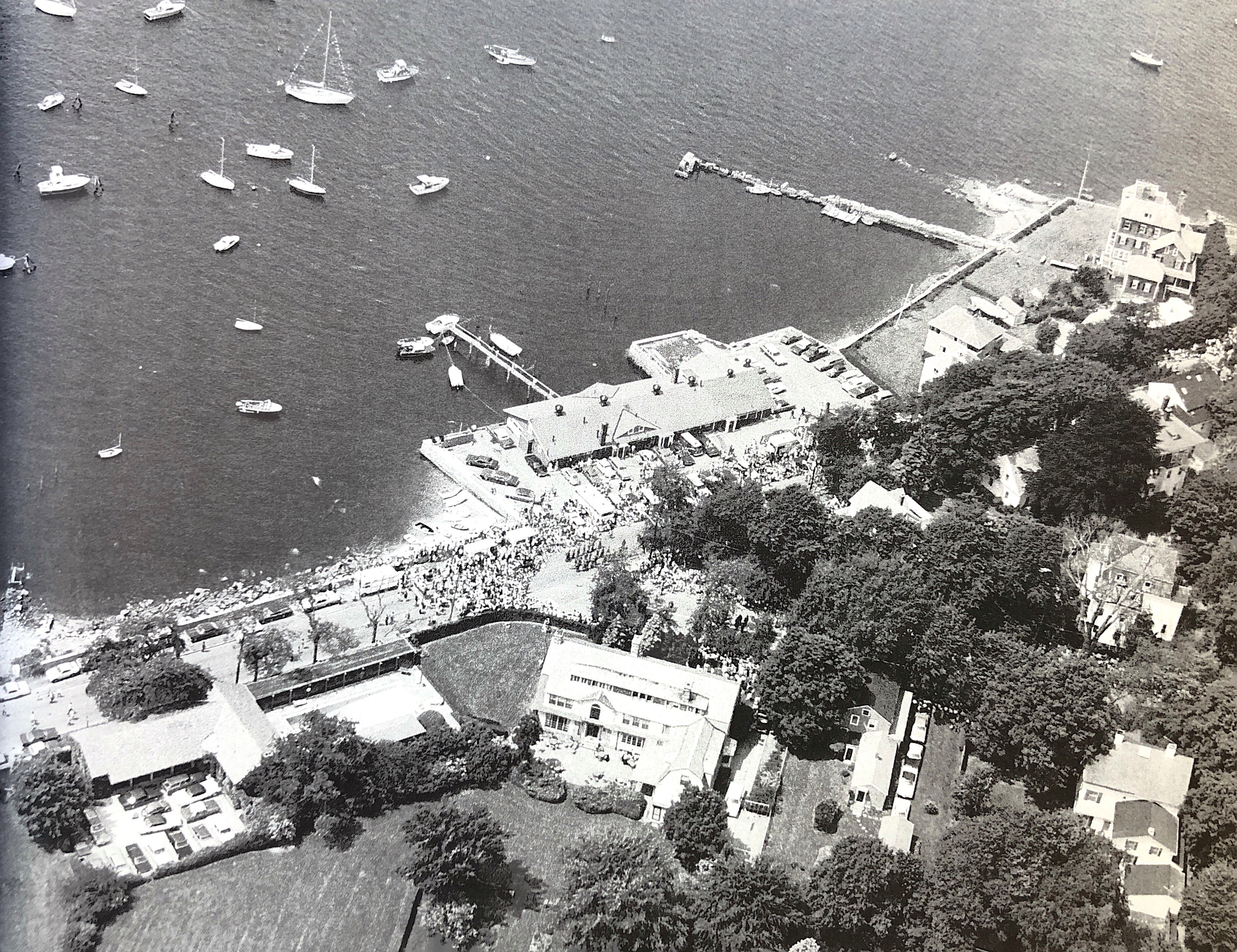

In the twentieth century, Bristol’s Fourth of July parade continued to transform as its crowds, and the resulting pressure to be a tourist attraction for the town, grew steadily. The committee became closely intertwined with the town board of affairs, engaging in the sort of political spats over budgets and logistics that consume many small towns. The 1930 parade drew an estimated 30,000 people, and ten times as many for the bicentennial in 1976. Today the parade continues to draw six-figure crowds. The schedule of events begins on Flag Day, more than two weeks before Independence Day itself, and includes everything from raffles and lotteries, to music concerts, a carnival, sports competitions, and even a beauty pageant. Naturally, corresponding committees and costs have ballooned in the perpetual fight over limited town resources.

There were plenty of minor town politics hashed out among the parade’s planning committee, but it remained resolved to stay above the fray of national political matters. For example, a longstanding practice barred campaigning politicians from participating in any official capacity in the parade, giving marching privileges only to those who had already been elected. However, the celebration has a history of being political dating back to Reverend Wight's first Independence Day sermon in 1785. He was a celebrated minister who grew his congregation significantly into the 1800s and continued his leadership at the patriotic exercises even after ending his service at the church. The Manual of the First Church in Bristol, R.I., reflected in 1873 that, “He took an active interest in the political questions of the day, and did not hesitate to introduce topics of this nature in his pulpit ministrations, which offended some whose views differed from his and led to their withdrawal from the Society.” Some of his critics signed a collective letter of protest and resigned from his congregation in favor of the Episcopal Church St. Michael’s. In 1836 the Bristol Phoenix described Rev. Wight’s preaching as commentary “in just the right pointed terms, the ultraisms of the day—[he] deplored that tendency to them which is so evident in our country at the present time.”

The political ancestry of the parade has continued throughout subsequent decades and centuries. The temperance organizations that dominated in the 1830s and 40s used electoral politics directly in their aims. In 1857, Antiques and Horribles parades began to emerge before dawn as theatrical satire of contemporary political figures. Such demonstrations appeared all over New England. The Bristol County Equal Suffrage League directed a horse-drawn float in 1915 featuring the Goddess of Liberty, 12 young women representing each of the states that let them vote, and a dejected representative from Rhode Island disappointedly displaying the state motto “Hope.” In 1971, Vietnam Veterans Against the War sent the town into uproar and the committee into chaos by suing after Parade Chairman Jerry Romano tried to prohibit them from marching. Federal District Court Judge Edward W. Day ruled in favor of the VVAW. Romano stated emphatically: “We feel that the parade’s purpose is to celebrate the independence of this country, and we have made it a practice in the past not to let anyone use the parade for anything political or commercial, or (to promote) any cause.” This claim is inaccurate as it is clear that the parade has had political qualities ever since its origin, as any meaningful discussion about American patriotism and history is bound to. Perhaps the committee’s pivot toward entertainment and commercial events over ones oriented toward meaningful historical commemoration is one element of their response to this undesirable reality.

Anthropologist Philip Leis, who studied Bristol’s Fourth of July Committee in the 1970s, considers the role of politics in the parade in his essay “Ethnicity and the Fourth of July Committee.” His study concerns “the American dialectic of liberty and equality,” exploring how such ideals are in tension given that one promotes assimilation and commonality while the other ties upward mobility to the freedom to take advantage of one’s individuality. Leis writes: “The rules say be like others; they also say access depends on using whatever personal resources are available”—he notes that this dichotomy is found to some extent in all human societies, but is particularly pronounced in Bristol’s meta-meditation on American identity. The substance of the holiday is inherently concerned with the principles of liberty and equality, as celebrants assume their most patriotic positions, even if that consideration is often now relegated to subtext.

In considering the committee closely, Leis contends that it “illustrates the situational nature of ethnic identity.” Ethnicity, seen as a dividing factor in the community for most of the year, was found to be less relevant in this context in which all committee members are “American,” and collectively emphasize “patriotism, unity, [and] commonality.” This unity, even if limited in scope, is meaningful insofar as it projects an optimistic understanding of nationhood and collective subjugation to a larger sovereign entity. Leis goes on to say, “By the members’ participation in the occasion—marching or observing, or being affected emotionally by the music, the spectacle, and the social gathering itself—the basic ingredient for belief is made possible. The ineffable is made real, the indescribable is communicated. In a word, the flag becomes something more than a piece of decorated material; it both represents and provokes the feeling the society exists.” This describes, perhaps, the ideal version of a patriotic celebration, in which entrenched rituals perpetuate the very same founding ideals from which they originated. To expect demonstrations of patriotism to function in such a way—save for the rare moment of collective exaltation—would be naive. As is abundantly clear to all of us in the twenty-first century, that the discussion over national identity and pride continues to be co-opted by third party groups, and that the dialogue is fraught with combative arguments, each side as pugnacious and self-righteous as ever.

But perhaps the appropriate takeaway from Leis is that the Fourth of July parade is at least somewhat successful is averting these conflicts. His study found that among members’ reasons for joining the committee, getting involved in the town affairs and helping out the community ranked slightly higher than the motivation of abject patriotism or commemorating historical events. Maybe there is something touching and fittingly American after all in the emphasis on local communities amidst the strife of national politics. Committee members “recalled how significant the annual event had been to them while they were growing up. It was the time their parents bought them new clothes, when friends came to visit, when there was a carnival in town; in effect, July Fourth was a pleasant memory that they wished to perpetuate for the next generation.” It seems like by the end of the twentieth century, the celebration had become more about the history of the parade itself than about the history of Independence Day. Let us not forget that it is history that has given us this day to celebrate, and in the battle over a national origin story, proud interpretation of facts must prevail.