New York's Capital Years: 1785–1790

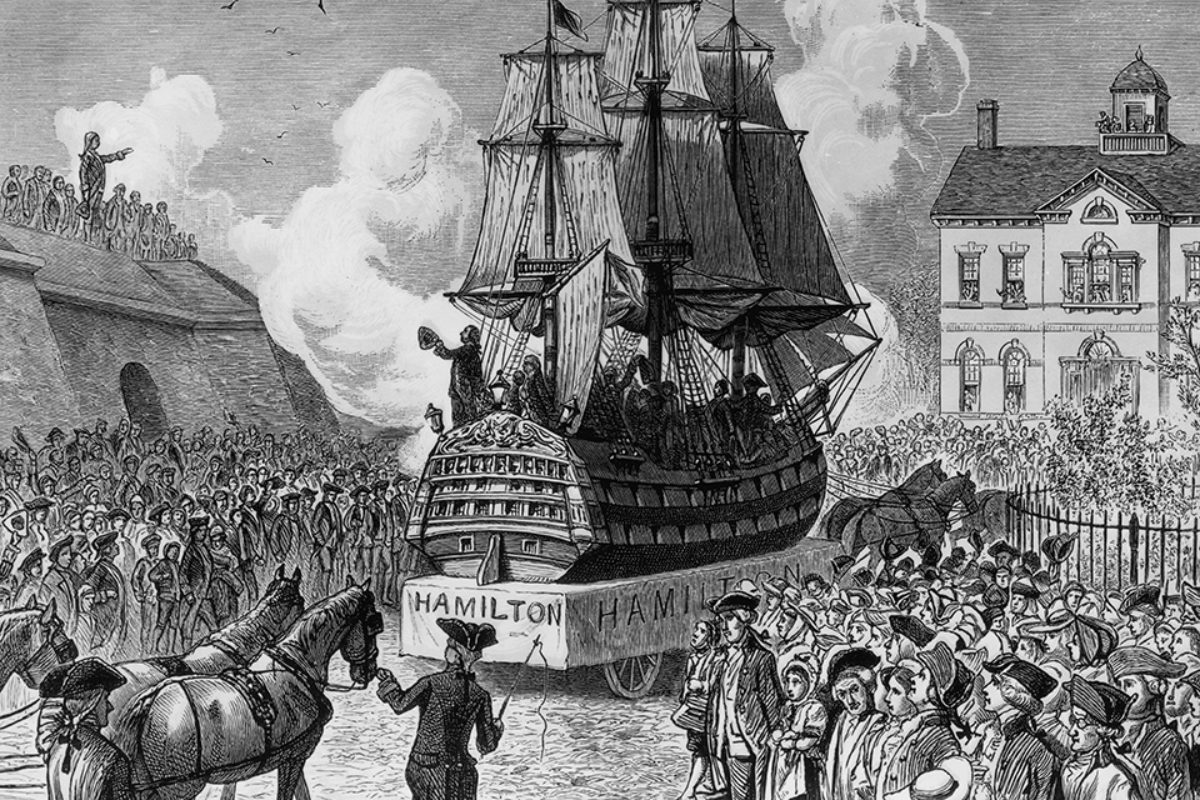

New York has always been among the most powerful urban centers in America, its outsized influence perhaps most pointed during the brief period in the founding era in which it served as the nation’s capital. In the years when New York housed the seat of the federal government, Congresses under two different names convened. First was the Congress of the Confederation, which was understood contemporaneously as a continuation of the colonies’ Continental Congress but was chartered by the Articles of Confederation. This system of governance, which had been defined in wartime, was soon deemed ineffective. In the summer of 1787, Philadelphia hosted the Constitutional Convention to draft a new document; the new federal contract was soon after embraced by the capital city. When an early vote for ratification was held in New York and the state’s rural representatives were revealed to oppose Federalism, New Yorkers launched into a Grand Federal Procession to demonstrate enthusiastic support for the document. On July 23, 1788, “Five thousand men and boys representing sixty-odd trades and professions showed up despite a light drizzle, all in costume and accompanied by colorful floats and banners proclaiming the happiness and prosperity that would follow from stronger national union.” Their route extended from the Commons (now City Hall Park) down Broadway to Great Dock Street (now Pearl Street). It ended in a banquet celebrating the hopeful future of a nation united under central government. New York voted to ratify the Constitution three days later.

This tour roughly traces both the physical route and the broadened story of that Grand Federal Procession, as it depicts the movement of New York City’s role amidst a transforming national government. The second governing body that convened in New York City was the first United States Congress, the same body which is in its 117th term today. George Washington’s inauguration in New York was met with a similar local enthusiasm for national pride. However, soon after, he and his government moved south—a result of one of the landmark compromises of the founding era. Many New Yorkers dismayed at this apparent loss of power, but as Wall Street continued to rise, it became clear that New York would retain its power in a different form of capital.

1. St. Paul's Chapel

St. Paul’s Chapel was built in 1766 as an extension of Trinity Church, whose Anglican congregation was growing rapidly in a time when American community life revolved around church. Situated on the relative outskirts of the city, St. Paul’s Chapel survived the fire of 1776, unlike Trinity, and thus became the parish’s primary location in the years until Trinity’s reopening in 1790.

Its notable congregants included many founding fathers, among them George Washington and Alexander Hamilton. The latter, thoroughly a New Yorker, visited the church regularly, contributing to its mission and ministry. Washington, who resided in New York during the first fifteen months of his presidency, is known famously to have attended a service at the Chapel directly following his inauguration, accompanied by Vice President Adams and both houses of Congress.

More broadly, this church demonstrates the influence of Christian values on the founding fathers. It is important to realize that, though the country’s architects had strong religious views and many of the colonies had established state churches, America’s founding documents outlined a distinctly secular nation. As adamant about the separation of church and state as the founders were, their Christianity remained a central part of their personal philosophies and inspired many of their political views. Church was a vital aspect of community life in the eighteenth century—and St. Paul’s a vibrant location of religious, intellectual, social, and political activity for New Yorkers. Situated at what was then the northern edge of the city, it looked out upon the active plaza of Broadway.

Many of the American colonies were founded on the principle of religious liberty and thus became home to several distinct denominations of Christianity, as well as communities practicing other religions or none at all. At the same time, nine of the original thirteen colonies had established state churches (all but Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware). Congregationalists reigned in New England, and Anglicans in New York and the South. However, when the time came to construct a national constitution, state religion was notably absent—in part because of the diversity and fortitude of so many distinct religious factions.

Another prime religious influence on the founders was, of course, Deism. Born out of the Enlightenment, this school of thought rejects many of the rites and traditions of orthodox Christianity in favor of a conception of God based on reason and nature and more compatible with classical liberalism. Deism rose in prominence throughout the eighteenth century, particularly in American universities which were keen to favor novel and radical ideas. Thus, most of the founding fathers—including Washington, Jefferson, and Adams—were educated in this tradition and brought the mindset to their political theorizing. There is no doubt that religion heavily influenced the founding of the nation, but it was never meant to be a theocracy, nor even expressly denoted to be of Christian origin. The references to God we have come to recognize in our national iconography are additions of later centuries. Nonetheless, this Episcopalian chapel nurtured the undeniably religious intellects of prominent New Yorkers in the Constitutional era.

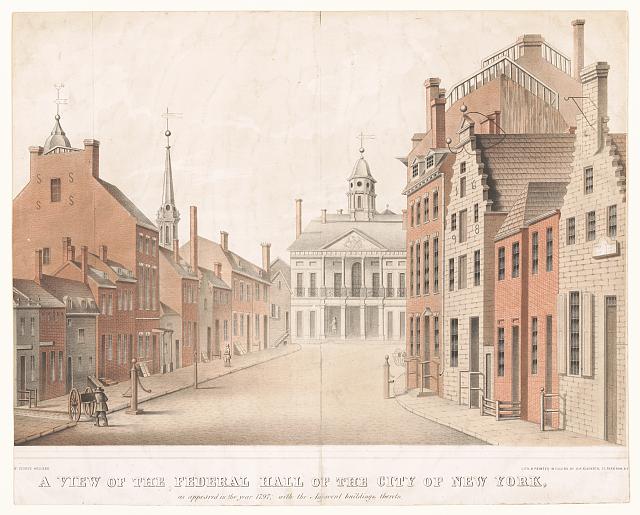

2. Federal Hall

The original building on this site, constructed 1699–1703, first served as the seat of government for the British Colony in New York. In 1765, marking a time of transition, it hosted the ad hoc Stamp Act Congress which convened to discuss the unfair taxation laws from Britain and ponder national union and independence. Later it became New York City Hall and then the meeting place of the Congress of the Confederation during its residence in New York. After leaving Philadelphia in 1783, and then meeting at temporary sites in Maryland and New Jersey, the Congress landed in New York City in the middle of its fifth session in 1785. With upwards of 33,000 residents recorded in the first census, New York was the largest city in the country, which lent it a form of automatic authority in becoming the national capital.

The Congress of the Confederation was a weak institution, granted very limited powers by the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union—America’s first attempt at a national constitution which was ratified hastily during the Revolution and soon after deemed a failure. From New York the Congress of the Confederation did, however, pass important legislation that significantly expanded the territory of the nation westward with the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

As New York’s power as de facto capital of the nation solidified, and spirits began to gather behind the adoption of a new federal constitution, City Hall closed for renovations in anticipation of this change. Congress moved out of the cramped space in October of 1788 and migrated around the corner to join the other government offices occupying the Walter Livingston House at 95 Broadway. Historians Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace write, congressional offices “vacated City Hall so the building could be converted into a suitable capitol by [Pierre] L’Enfant. He gave it a complete facelift and turned its interior into a showcase of plush, some said extravagant, neoclassicism.” The building reopened as Federal Hall in March of 1789 to host the first meeting of the United States Congress under the new constitution.

In April of 1789, with the fervor of a renewed national government, New York welcomed George Washington to be inaugurated as America’s first president. Upon arrival in the city on April 23, he was greeted with a grand parade, crowning the celebrations that marked his entire journey up from Mount Vernon. On Thursday, April 30, Washington was inaugurated on the steps of Federal Hall. To mark the pride New Yorkers felt in the new national government, and their prominent role in it, another festivity was held. As Burrows and Wallace recount, “That evening, visitors and residents jammed the streets to gawk at ‘illuminations’—huge backlit transparent paintings of patriotic subjects erected here and there around the city.” An article in Harper’s Magazine commemorating the first inauguration adds that “window-panes broke with the joyous firing, bunting floated from house and tree, and all sorts of merrymaking stuff showed the sentiments of New York when Washington entered.” From the renovation and renaming of Federal Hall, to the continual joyous celebration, it is clear that New Yorkers were honored and enthusiastic about being residents of the nation’s capital.

After the capital’s move to Philadelphia and Washington’s departure from the city in 1790, Federal Hall reverted to housing local government offices. It was demolished in 1812 and replaced with a new building in 1842. Federal Hall is now a memorial in the National Parks Service and is open to the public in the absence of covid restrictions.

3. 41 Hanover Square

At 41 Hanover Square once stood the offices of the Independent Journal, a founding-era newspaper best known for publishing the Federalist Papers. The first installment of what became a remarkable and impassioned campaign for Constitution adoption ran on October 27, 1787, in response to criticism of the Constitutional Convention that had emerged after its conclusion in September. Alexander Hamilton, author of the first Federalist Paper, was soon joined by James Madison and John Jay—collectively under the pseudonym Publius—to publish a total of 85 essays in favor of the Constitution. The Federalist Papers provoked robust public discussion about the implications of this new document, and the collection is now regarded as a fundamental supplement to our founding documents.

The essays were published in three New York newspapers: the Independent Journal, the New-York Packet, and the Daily Advertiser. The offices of the former were located in Hanover Square, along with the other papers of the time including the New York Gazette, and the New York Mercury—making this area known as Printing House Square before the rise in publishing power of the nearby section of Park Row. New York’s publishing industry continued to grow throughout the coming centuries, and remains an integral part of the city to this day.

The importance of this story at the time, however, was in denoting New York City as a stronghold of Federalist support. In New York’s first vote on ratification, in April of 1788, while the state overall rejected the Constitution, “Manhattan produced a Federalist landslide” of 96%. Many residents of the city didn’t perceive the risk in surrendering any power to a central federal government that was usually at the heart of the opposition. Already the acting capital of the nation, New Yorkers assumed that Federalism would only serve to increase the city’s power, and thus embraced the concept early on.

Alexander Hamilton, New York’s favorite founding father, was instrumental in securing this position. Hamilton became known for his support of a strong federal government through his vocal involvement in the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787. These views often isolated him from more moderate counterparts who did not seek such extreme change to the Articles of Confederation, including the other two delegates from New York, John Lansing and Robert Yates. Though the document ultimately drafted at the convention presented a weaker federal government than that which was imagined by Hamilton, he remained a fierce proponent for its adoption.

In the push for state ratification, Hamilton and his allies were at odds with New York Governor George Clinton, whose more rural faction was wary of increased federal power. Hamilton advanced the same arguments in the Federalist Papers that he used more pointedly to convince his colleagues to vote for ratification. In Federalist 1, Hamilton writes: “Yes, my countrymen, I own to you that, after having given [the Constitution] an attentive consideration, I am clearly of opinion it is your interest to adopt it. I am convinced that this is the safest course for your liberty, your dignity, and your happiness. I affect not reserves which I do not feel. I will not amuse you with an appearance of deliberation when I have decided. I frankly acknowledge to you my convictions, and I will freely lay before you the reasons on which they are founded.” There was little ambiguity in his position, further developed in the subsequent expository essays, and it is clear that Hamilton, through publication and personal persuasion, was instrumental in advancing the cause for the Constitution in New York.

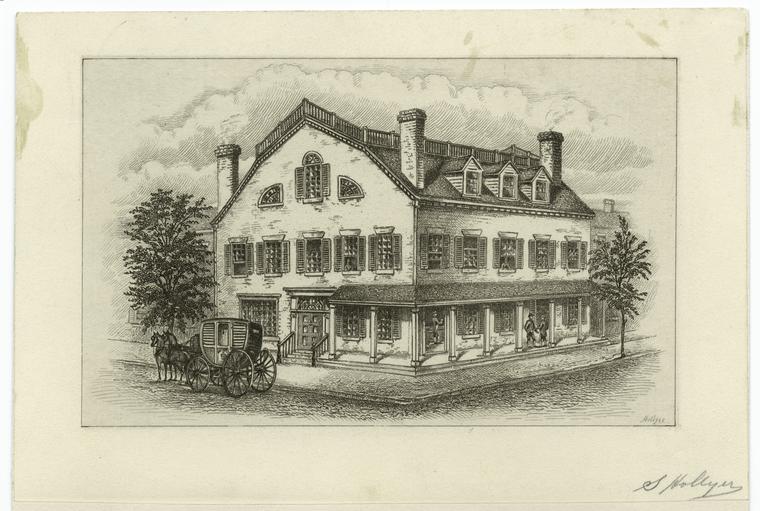

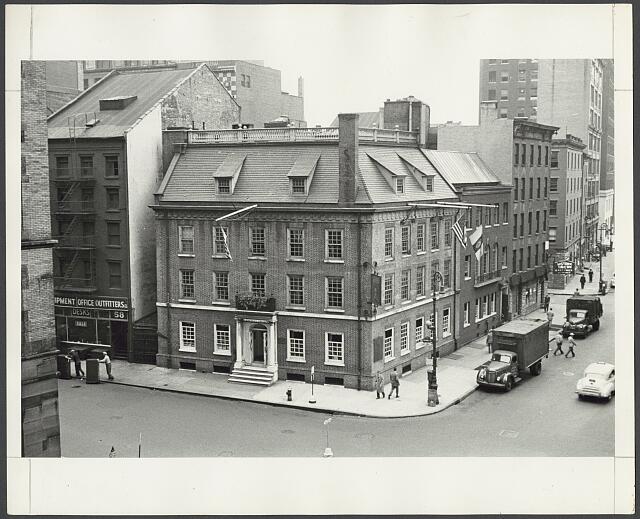

4. Fraunces Tavern

Perhaps New York’s most famous surviving building of the founding era is Fraunces Tavern, which has continued to operate as a restaurant and now is home to a museum as well. It is best known for being the site of George Washington’s farewell speech to the Continental Army on December 4, 1783. Some also claim that Fraunces Tavern was also once briefly the seat of the US Government, housing the final meetings of the Congress of the Confederation, citing information that the Congress joined other departments located around town when City Hall went under renovation. It is known that the tavern leased space on its upper floors to such government offices as the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Department of War. However, a letter dated February 1, 1788 from John Jay and Henry Knox informs the Commissioners of the Treasury that their respective offices had found new housing in the home of Walter Livingston (at 95 Broadway), and invites the offices of the Treasury to join. The Fraunces Tavern Museum corroborates that “the three departments were tenants until May of 1788.” Pierre L’Enfant’s renovations on City Hall began in October of 1788, suggesting that when the Congress moved in with the other offices, it was at their new Broadway location, not at Fraunces Tavern.

By this time, the new Constitution had already been ratified by eleven states and was set to take effect in the Spring. Thus, enthusiasm for the “lame duck” Congress had waned. It is not certain that in these sessions a large enough quorum was assembled to constitute formal proceedings. Even in the absence of certainty on the meeting location of Congress, Fraunces Tavern was an essential gathering place for many figures in the founding era.

In the eighteenth century, a tavern served many functions: It was part boarding house, office building, restaurant, bar, and entertainment hall—always a lively center of community life. Much like the church inspired their lofty ideals by day, the tavern saw the founders in boisterous debate by night. Samuel Fraunces opened this tavern in 1762, and throughout the revolutionary era it attracted both locals and tourists with its atmosphere of exuberant hospitality and consideration of the day’s most compelling issues of wartime distress and political theory. When New York City was the nation’s capital, it of course drew many important figures to come witness the eminence firsthand. Among them was painter John Trumbull who came to New York to study the faces of the founding fathers for his later work “Declaration of Independence.” He and other visitors of distinction would have likely stayed at a place like Fraunces Tavern.

Like many wooden buildings of its era, Fraunces Tavern suffered damage to numerous fires and after each was rebuilt. As the museum describes, “By the end of the 19th century the building bore little resemblance to the original structure. Two new floors and a flat roof were added.” In 1900, the Sons of the Revolution in New York bought the building and embarked on an ambitious restoration project to dismantle the top two floors and return to the original roofline. The design of the resulting structure is highly speculative, as no definitive image of the original can be located. Such unsubstantiated and extensive renovations call into question the justification for claims that the building is among Manhattan’s oldest.

5. Bowling Green

New York’s Bowling Green played a prominent role throughout the colonial and revolutionary eras—perhaps best known for the statue of King George III on horseback which was toppled by patriots on July 9, 1776. It is also New York City’s oldest allotted public space, dating back to 1686, and was formalized as a park in 1733. The area was designated to serve primarily the purpose of public recreation. The adjacent Battery also transitioned into this role of public common, following its military use in the Revolution.

This spirit was embodied well in the Grand Federal Procession on July 23, 1788, which extended from what is now City Hall Park, down Broadway to Bowling Green, and on to Great Dock Street. Pictured here is the Federal Ship Hamilton, a horse-drawn scaled-down frigate which accompanied jubilant crowds celebrating the Constitution. This particular parade float was “dramatic testimony to Hamilton’s effectiveness in linking adoption of the Constitution to the city’s economic well-being.” It exemplified the enthusiasm with which New Yorkers would greet the new national government, of which they saw themselves as the obvious center.

Three days later, New York ratified the Constitution in Poughkeepsie by the narrowest margin of any state. Just weeks before, New Hampshire had become the ninth state to ratify, enough to put the new Constitution into effect; Virginia immediately followed as tenth, an acceptance which crystallized the inevitability of the new national government. Nonetheless, New Yorkers were enthusiastic in celebrating official ratification, as “jubilant crowds again surged through the streets.”

The public demonstrations were not all positive. Just a few days prior to the Grand Federal Procession, John Lamb, a fervent anti-federalist and general in the continental army, had “led a party of Antifederalists down to the Battery to burn a copy of the Constitution.” Burrows and Wallace remind us that overall, New York City was strongly in favor of the Constitution and these protestors “had to fight their way out of the angry crowd that surrounded them.”

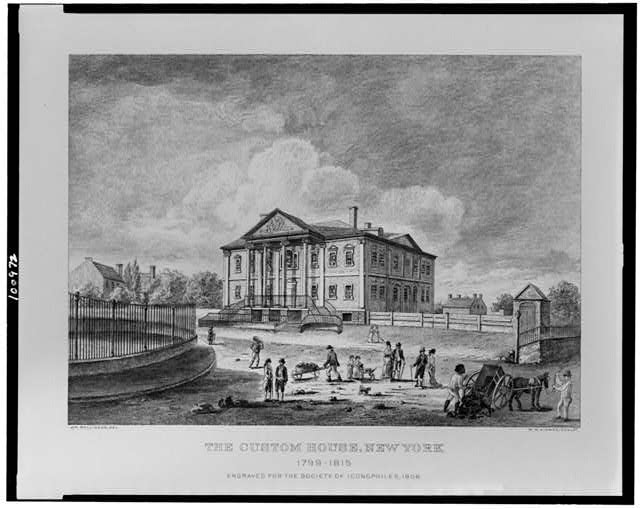

In fact, New Yorkers were so excited by the prospect of the new federal government that in 1790 they erected “Government House” (demolished 1815) overlooking Bowling Green, on the site of the Battery’s recently demolished Fort George. This Georgian mansion was intended to be the executive residence for Washington and subsequent presidents. The local fervor around cementing a position as the nation’s capital was such that “There was even talk about turning lower Manhattan into the federal district envisioned in the Constitution, complete with government offices, residences, parks, and gardens; one plan designated Governors Island, just across the harbor, as the site for a presidential mansion.” New Yorkers’ dreams of embodying this grand capital city never materialized as the seat of government was moved to Philadelphia in 1790, as an interim location for the long term home of Washington DC which was completed 10 years later.

6. Alexander Macomb House

After George Washington was inaugurated at Federal Hall and went to worship at St. Paul’s Chapel, he moved into the presidential residence on Cherry Street. This was known as the Samuel Osgood House (for its owner), or the Franklin House (for its cross street), where Washington lived for the first ten months of his presidency. On February 23, 1790, George and Martha Washington moved into the home of Alexander Macomb at 39 Broadway, which the government rented on their behalf. This house was grander and more favorable in many regards; as outlined in Harper’s Magazine: “The house, the finest private dwelling in the city, in the most fashionable quarter, was a story higher than the Franklin—four stories high—and larger in every way. It was of double brick, the front handsome. The usual brass knocker was on the heavy entrance-door, which opened immediately upon the street but for a short flight of steps. Long glass doors led from a drawing-room to the inviting balcony, and from the rear window the eye delighted in an extended view of the Hudson and the Jersey shore.” First built in 1786, the Macomb House was demolished in 1940. An office building currently occupies the address, adorned by a plaque installed by the Daughters of the American Revolution commemorating the presidential residence.

At the time New York City was still thought of by many as an English stronghold in a young rebellious nation. This association was underscored by the dominance of the Anglican Church (renamed Episcopalian since the Revolution), Hamilton’s public defense of monarchy and central national power, and that the city was the final place for British troops to occupy when the war ended. Many Americans were skeptical of the loyalism of New York City and distrusted the cosmopolitan and commercial nature it had already come to embrace. Thus, many rural Americans, particularly in the southern states, did not want New York to remain the capital under the newly renovated federal architecture. Many wanted to prevent New York City from becoming the federal district outlined in the Constitution (Article 1, Clause 17) and defended by Madison in Federalist 43. Of course, New Yorkers were resistant to the idea of giving up the power they held, but Hamilton orchestrated a compromise which secured a concession from southern states that he deemed more important to the health of the union overall. It was agreed upon by Congress that the federal government was to assume the war debts of the states (passed as the Funding Act of 1790), in exchange for the passage of the Residence Act which named a site on the Potomac River to be home to the nation’s capital district.

The Residence Act was passed in July and, “On August 12, 1790, Congress met for the last time in Federal Hall. Two weeks later, on August 30, Washington stepped into a barge moored at Macomb’s Wharf on the Hudson and left Manhattan, never to return.” Washington, having “had that preference for being unobserved that develops at times into a longing in a man whose life is spent in public,” would have liked a “concealed departure” from the city, but instead received a “flurry of publicity.” Such public forms of community ceremony had become typical of New Yorkers, and Americans, in this era of national birth and pride. New Yorkers mourned losing the title of capital city, but bounced back quickly due to their inalienable power realized as the nation’s foremost commercial center. As Burrows and Wallace write, “Henceforth the United States would have two centers, one governmental, the other economic. The separation of powers, as emphatic as anything in the Constitution, had no parallel in the Western world.” New York maintains this distinction today, and remains a more magnetic urban center than Washington, even in the absence of the federal fanfare it once so eagerly awaited.