Farming in Little Compton

Introduction

Each chapter of the human history of this land—known as Little Compton since 1682—points to agriculture as a central pillar of the community. Beginning with the Sakonnet people and then following the English settlers as they grew from a group of struggling homesteaders to a vibrant community attracting outsiders, this tour tracks the evolution of farming in Little Compton. Many have remarked that to travel to Little Compton is to travel back in time; moving through the town today, one will notice that many of the old stone walls are still in active use. While certainly changing with the times, Little Compton has remained a vibrant farming community well into the 21st century. One reason this character has persisted here is because Little Compton has always been more than an insular farming community. But even as residents began to leave town for the world at large, they have often remained bound to its landscape and pulled back by the magnetic force of the community. Indeed, I continue to find myself drawn back to this place after several youthful summers spent here working on local farms. Longtime residents all agree there is something enchanting about the landscape.

Since the story of a small farming community cannot be told through sites concentrated around the town center, this is Histourian’s first bike tour. The route is long, roughly 17 miles, so bikers are encouraged to allocate their time accordingly, and plan to rest and explore at one or more of the stops (which include a beach, a farmstand, and woodland trails). The route is a loop and can be done in either direction and starting from any point, but the written narrative is best suited to beginning at the Commons and proceeding clockwise: down South of Commons Road toward Wilbour Woods. Geography tends to supersede chronology when I map these routes, but I’ve done my best to present a coherent story of the progression and persistence of agriculture in this special town.

1. The Commons

This land was allotted for the Town Commons in the spring of 1677 by four English settlers in Duxbury, Massachusetts who divided it into profitable, workable parcels after the southern theater of King Philip’s War closed. Seventy-four private lots were surveyed, mapped, and sold to prospective homesteaders; thirty-two buyers got two parcels each, with ten left on reserve for later sale. The Commons were to hold a burying ground, communal livestock enclosure, and meetinghouse. During the first chapter of the town’s history, the population was primarily dispersed along the Great West Road (now West Main), which ran north to south roughly parallel to the Sakonnet River. The first proprietors tended to own ribbon farms, long and skinny properties that connected to both the road and the river. Establishing subsistence agriculture on this land was “a rugged undertaking,” and for the first few decades, labor was devoted almost entirely to developing the family farm.

To the great disappointment of Plymouth Colony, which governed with strictly Puritan demands, Little Comptoners did not build a meetinghouse on the Commons until 1694. It was not until the early 18th century that Meetinghouse Lane was built, making the Commons directly accessible from the Great West Road. Not until 1701 did the town finally hire a full time minister to preach in this church. This hesitance in embracing established religion is somewhat indicative of Little Compton’s role in the tension between Massachusetts and Rhode Island, both of which claimed it as part of their territory. The town community was much more successful in rallying around agriculture. The little deference to Plymouth that was shown was on matters of procedure. In 1683, Little Compton had its first election; in accordance with the colonial guidelines they selected a “constable,” “grand enquest,” and “deputy.” But as local historian Janet Lisle puts it: “from the outset, the town made a point of deciding local issues for itself.” The self-sufficient spirit of Little Compton paid off during the Revolutionary War, when the town’s regular markets in Newport were clobbered by the British occupation. In response to this, Little Comptoners returned to their homesteading roots and produced substitutes for virtually all imported goods (except tea). Again in the War of 1812, and in subsequent periods of distress, Little Comptoners made the pivot toward self-sustaining production with relative ease.

Support for agriculture has been a central tenet of the community throughout the town’s long history. But what really makes Little Compton special is that it has always looked beyond the stereotypes and assumptions of a rural community to reach for a more resilient and expansive culture. For example, though the Rhode Island Country Party dominated state politics in the years after the Revolution, Little Compton was a holdout against this anti-federalist populism. In fact, it was one of just two towns to have supported the Constitution in the state’s first vote on ratification. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Little Compton boasted an unusually high literacy rate, especially among women. Girls and boys balanced school with their ongoing responsibilities at home on the family farm. By the time the state first intervened in public education in 1828, Little Compton already had robust systems in place but welcomed the extra funding for its school. There was also widespread interest in issues of social and political reform, including notable abolitionist circles active within the town community.

This interest in broader issues did not come as a sacrifice to the importance of agriculture or a move toward a manufacturing economy or cosmopolitan culture as it did in many places in the northeast throughout the nineteenth century. Little Compton remained decidedly agrarian in its economy and culture: In 1880, 10,500 of the town’s 13,376 acres were cultivated (78.5% of the total land area). The median size of a farm was 48 acres and few were run by someone other than the landowner. By the end of the nineteenth century, Little Compton was still a community of family farms, though the nature of these farms had continued to evolve, as will be explored in the rest of this tour.

2. Wilbour Woods

Some evidence suggests that the Sakonnets, a tribe of the Wampanoag people, inhabited this land for up to 10,000 years before first contact with the Europeans. The Sakonnets are primarily known as a fishing culture but it is likely that they engaged in at least some level of cultivation of plants native to the area. This swamp, now known as Wilbour Woods (named after Isaac Wilbour, who himself called it Awashonk Woods) was the winter home of the Sakonnets. Awashonks (spelled sometimes with the terminal ‘s’ and sometimes without) was their sachem, a title similar to chief or queen. Her rule over this land is memorialized on a rock at the entrance. If you look closely you can make out the engraving: “in memory of Awashonk, Queen of the Sogkonate, friend of the white man.”

It is difficult to know with great certainty anything about Sakonnet farming, given that they had no system of writing. But based on historians’ interpretations of Europeans’ accounts of the landscape they encountered upon their arrival, we can tell that “in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and undoubtedly long before, areas open and cleared for settlement, cultivation, or other native purposes were common along New England’s seacoast.” It is also known that Narragansett Bay was the most heavily settled area of native New England. Though they often moved seasonally, “few New England Indians were by preference nomadic or forest dwellers; most were villagers, and had been for centuries.” This information suggests that agricultural practices were entirely likely among the Sakonnet people.

At the very least it can be said that they created conditions preferable for select species to thrive. The soil was undoubtedly difficult to till, especially without any metal tools or draught animals. Nevertheless, southern New England was known among native populations to be a fruitful land. Wintering in the fertile swamp, Sakonnets harvested a great variety of edible roots and seeds, contributing to a diet far more diverse than that of their European counterparts. Historian Howard Russell writes that the Indian got such a diverse diet from a combination of “woods, waters, and his cultivated fields.”

While the woods gave high foraging and game yields, the most dependable source of food seems to have been the waters. Sakonnet has been translated as both “place where the water pours forth” and “fishing place cove”—either way the importance of fishing to the culture is obvious. But Russell is careful in reminding that, “by the time descriptions of New England’s Indians were set down in writing, except for eastern Maine they had gone beyond the stage of full dependence on fishing, hunting, and gathering...We must not forget that for the most part the New England natives were agricultural.” Their crops included berries, pumpkins, beans, corn, grapes, melons, artichokes, and tobacco. In adapting wild plants for cultivation, varietal selection and rudimentary breeding seem likely.

Technological differences, particularly due to the lack of naturally occurring metal ores (except a small amount of copper), were a big factor that distinguished the early agriculture of the Native Americans from that of the Europeans. Once Europeans crossed the Atlantic and began to make settlement claims in North America, both cultures adopted elements from one another. Native Americans in southern New England observed oxen ploughs and metal hoes among the Englishmen. Previously, natives’ tools had been made out of stone, wood, and quahog shells. Using such materials required a lot more labor than their iron and steel counterparts. Adopting technology and practices from English farmers allowed Native Americans to be more efficient with their labor and opened new doors for agricultural potential.

Metal tools also enabled new methods in clearing forests. Before the Europeans, felling trees was an intense and laborious process that usually involved a combination of girdling and burning. Native Americans did so to facilitate nut production and deer browsing, as well as to plant crops. Large cornfields are known to have been prevalent across southern New England long before European arrival. European tools and motivations took land clearing to new heights and, by the eighteenth century, there was virtually no remaining old growth forest in Little Compton. It is said that the town was once so clear, one could have seen all the way to Sakonnet Point from the Commons. Under the European model of land valuation, swamps like the one Awashonks and her people inhabited were relegated to be woodlots serving farms that thrived on drier, more arable land. For as long as the Sakonnet people remained a distinct culture and population, they inhabited this swamp, appreciating the fertility of Dundery Brook like the Europeans never would.

3. Sakonnet Point

Sakonnet Point was the summer destination of the people after which it is named. It was typical of southern New England Native American tribes to move closer to the water during the summer months both because it provided better fishing opportunities and for similar reasons that people continue to do so today: in pursuit of a “pleasing outlook” and opportunities for leisure. Russell writes of New England tribes: “They would very likely spend a few weeks at the seashore or at a great waterfall, seeking fish to cure—and also to enjoy pleasant company, games and contests.” Net sinkers and projectiles are among the archaeological remains found from the Sakonnets that demonstrate the group’s skill in fishing. Though European settlers supplanted the Sakonnet territory on the point as early as the seventeenth century, these new settlers did not establish a flourishing fishing industry at there until the nineteenth.

Rather, Sakonnet Point was of importance to them in the access it provided to Aquidneck Island via ferry. There were a number of ferries along the Sakonnet River: among them were one at Taylor’s Lane, one near Brown Point, one by Fogland Beach, and one at Stone Bridge. But transport from Sakonnet Point provided the shortest route to Newport, which was a thriving shipping port and dominant city in the region during the colonial era (See: Newport tour). Though the town was claimed by Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1747 when it officially joined Rhode Island, Little Comptoners found trade with Boston “far more arduous” than trade with Newport. To sell farm surplus or purchase equipment from Newport only required a short ferry transport across Sakonnet Passage; whereas to sail to Boston, one had to skirt the tip of Cape Cod (overland travel was equally difficult). Thus, Little Comptoners were much more integrated with Rhode Island markets than with Massachusetts ones and “had always felt closer to Rhode Island than to its strictly governed northern neighbors.” It was a complicated situation because both Massachusetts (according to a 1629 document) and Rhode Island (in its 1663 charter) claimed the area via English authority. In 1692, a group of town residents led by John Almy petitioned the Rhode Island State Assembly to clarify its eastern border without alerting Massachusetts. When Massachusetts Bay Governor William Phipps found out, he ordered the arrest of the petitioners, who managed to resist. The town didn’t succeed in joining Rhode Island for another 50 years.

Contrary to the thickly settled area we see now, Sakonnet Point remained sparsely populated for a long time. One large farm occupied the whole space; originally known as Seaconnet Farm and then bought by successful New Bedford whaling tycoon William Rotch at the beginning of the 1800s (this name will be familiar to readers of the New Bedford tour). Lemuel Sisson, a farmer from Aquidneck Island, crossed the Passage to run Rotch’s farm. Along with prosperous farming experience, Sisson brought Methodist traditions and abolitionist ideas that quickly took root in the town. The farm had both livestock and produce. Additionally, there is known to have been a large windmill situated between Round and Long Ponds (pictured here) that ground up corn and wheat. Rotch’s property deed is still referenced in today’s town charter, in preserving the right of residents to access Sakonnet Harbor.

In the nineteenth century, Sakonnet Point began to transform into a more active fishing village. The first half of the harbor’s breakwater was built in 1838 and it was extended in 1899. This safe harbor caused fishing in the area to rise to levels not seen since the reign of the Sakonnets. Furthermore, the West Island Club boasted unparalleled bass fishing opportunities, just off the tip of Sakonnet Point. It quickly gained prestige, attracting prominent men to town including presidents Chester A. Arthur and Grover Cleveland, as well as wealthy banker J.P. Morgan. The club’s rapid ascent in social status led to overfishing which quickly depleted the bass population. After a brief stint in rum running during Prohibition, the West Island Club fell into disrepair and eventually washed away. Moving into the early twentieth century, the point “evolved into a scruffy fishing village,” a character which has now largely been replaced by more posh summer residences, though the harbor remains an active commercial fishing locale.

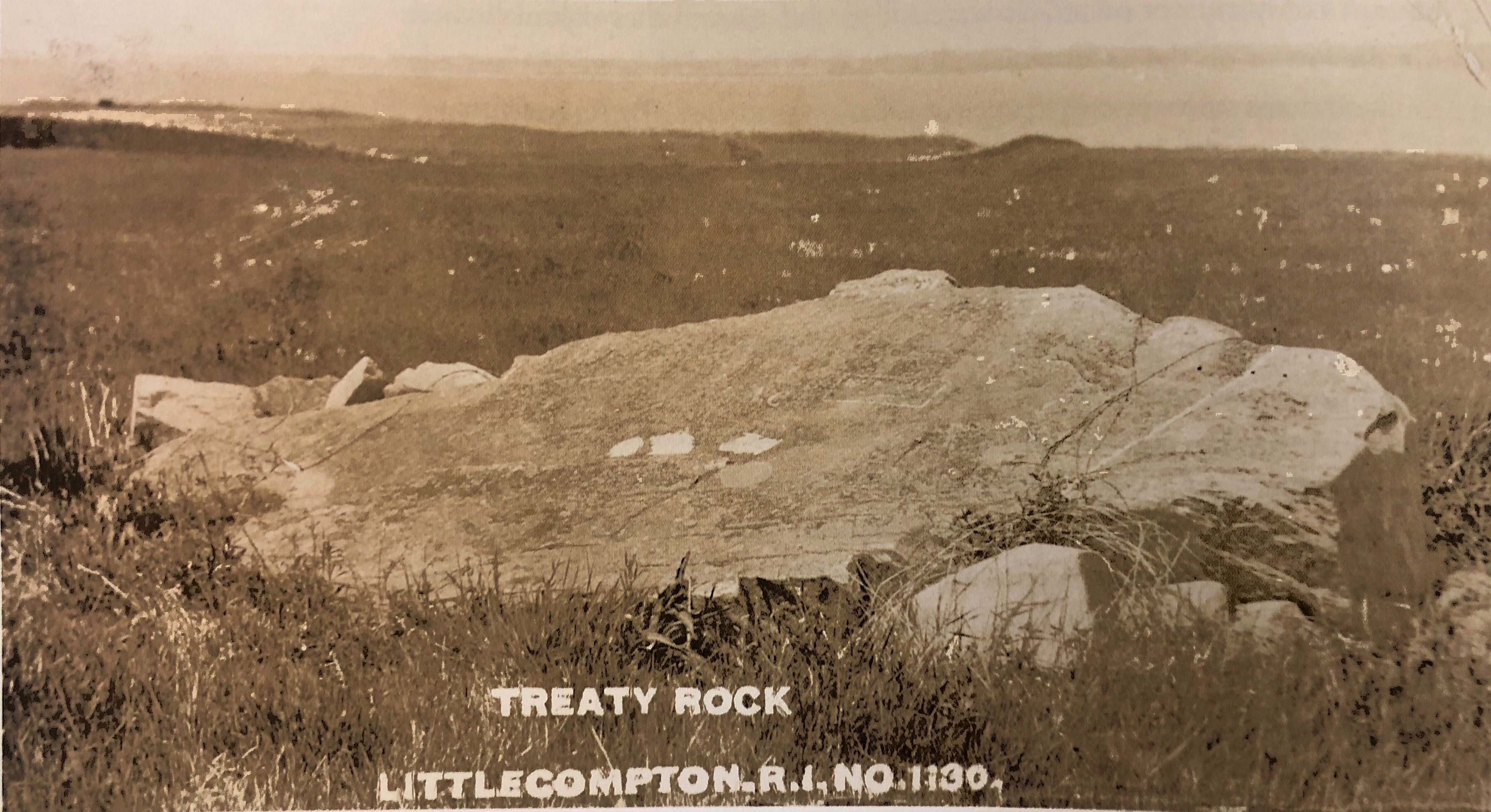

4. Treaty Rock Farm

Treaty Rock Farm is so-named for the agreement made here on June 8, 1676 between Awashonks, sachem of the Sakonnet, and Benjamin Church, local English homesteader. In the prior year, the clashes between Native American tribes and encroaching European settlers that had been common ever since the arrival of the latter, had escalated into war. Metacomet (sachem of the Wampanoag, also known as King Philip) had a strategy dependent on a tenuous coalition between disparate Native American groups that had longstanding conflicts among themselves. In the spring of 1675, he tried to secure an alliance with Awashonks, warning that war with the colonists was imminent due to escalating land controversies. Awashonks’ primary experience with English settlers had been her largely civil relationship with Benjamin Church, who arrived in her area in 1674 to homestead. In the face of impending war, Church cast Philip as an antagonist in an attempt to secure the support of Awashonks on behalf of the English. So far, she and Church had maintained a sufficiently cordial relationship and viewed one another as allies. Thus, Awashonks tried to hold back her warriors from fighting alongside King Philip. When war fully broke out in June of 1675, Church enlisted with Massachusetts as a military leader and began a trek southward to consult with the Sakonnets. At Punkatees Neck (Fogland), Church was ambushed by a group of local Indians that had indeed ended up joining King Philip’s cause; all escaped unharmed but the alliance now seemed untenable.

As the war escalated, both parties vacated the area temporarily—the Sakonnets sought shelter from the war zone, while Church went on fighting. Having both returned to the area by the summer of 1676, Church and Awashonks met at Treaty Rock and hashed out the events of the past year with suspicion, but eventually rebuilt trust. Church promised to vouch for the Sakonnets before the Plymouth Court, which eventually let them return to their ancestral lands. To stay afloat in the English economy that had now been established in the area, the Sakonnets sold off a lot of their land. Over the next half century, they assimilated in large part to the economic, religious, and legal systems of the settlers, but retained many aspects of their original culture. The Sakonnet population dwindled as many succumbed to disease, men took on dangerous jobs, and women were incentivized to intermarry. By 1762, only about eighty years after Awashonks’ death, it is estimated that just 105 Sakonnet people remained.

As Euro-American culture replaced that of the Native Americans, the settlers shaped the landscape in lasting ways. Most transformative was the massive clearing of land and erection of stone walls to mark property lines and create grazing pastures for livestock. As Lisle tells us, “The present day layout of the town still conforms to the contours of these first labors.” These first labors steadily built up the town’s agricultural business: “Every family with any sort of plot grew turnips, squashes, and potatoes, storable root vegetables that would see them through the winter. Most families owned at least one cow. Small orchards, especially apple and pear, were tucked into available corners. Berry bushes were encouraged in back lots and along stone walls.” Oxen and horses retained a role on farms well into the twentieth century since tractors did not come into widespread use until late. As products from the western frontier—where land and opportunity seemed infinite—began to outcompete local goods in the northeast, Little Comptoners had to adjust their farms to the changing modern reality.

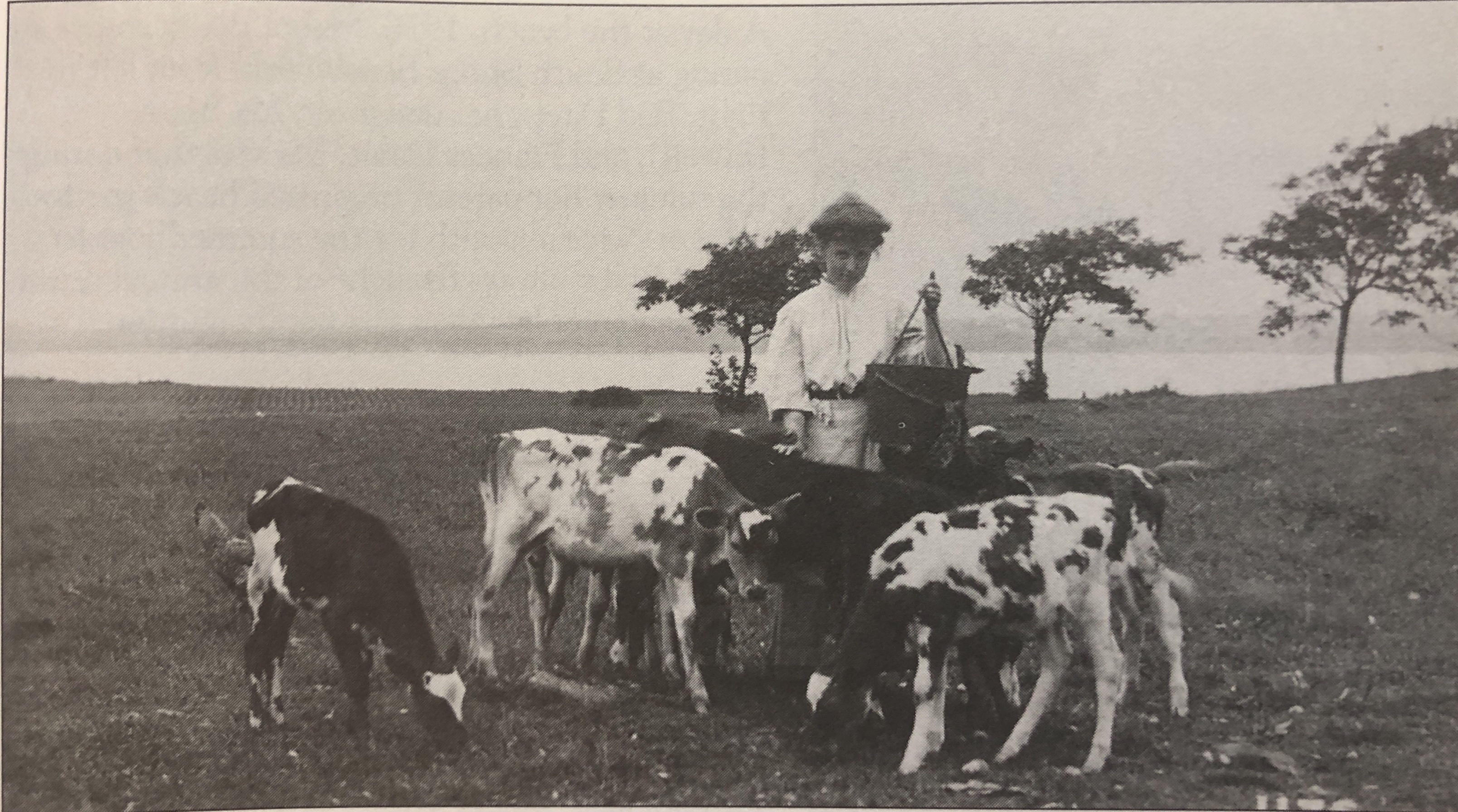

5. Walker's Farmstand

To remain a viable farming community in the modernizing world, it seemed essential to scale-up production. This was particularly difficult in a place with no extra acreage to give and a weary Yankee population declining in family size. An influx of able and ambitious Portuguese immigrants helped with the latter problem, but it remained difficult for Little Compton to compete with farms further west. Milk, cream, eggs, and butter became key products for Little Compton farmers because they were more resilient against competition from westerns ranch suppliers due to the difficulty of refrigerated shipping. Market wagons came into popular use, transporting raw produce and value-added products to nearby population centers in Fall River, Providence, and New Bedford. Remember that these nineteenth century wagons were ungainly vehicles, pulled by horses on uneven dirt roads. Even as Little Compton adapted to the times, it remained old-fashioned in practice and spirit. As modernization swept over the nation and many New England towns had to pivot toward new modes of industrial production to stay prosperous, Little Compton largely remained “a calm, unchanging center at the eye of the storm.”

Some children of Little Compton farm families left town to pursue economic opportunities in the world at large. Many succeeded in making a name for themselves. Among them was David Sisson, “by far the wealthiest man in town during the 1850s and 1860s.” After leaving his father’s tenant farm, Sisson became a prosperous businessman in the Providence and Fall River manufacturing industries. He then directed money that he had only been able to make by getting out of agriculture back into his family’s farm property on Sakonnet Point, where he built the magnificent Stone House in 1854. Sisson was not the only one to bring city dollars into the Little Compton farming community. In fact, much of the persistence of the town’s agricultural character today is due to money from elsewhere that enables long-time residents to continue a lifestyle on small family farms that became economically unfeasible without such support long ago. This is due to some indiscernible combination of an intrusion of oblivious but deep-pocketed summer people and continued earnest and active community support for agriculture. It is common in Little Compton today for residents to operate hobby farms even when their primary source of revenue comes from elsewhere.

Of course, there are a number of commercial farms whose owners continue to depend on razor thin produce margins for their livelihood. One way many farms have managed to stay afloat in such an economy is by focusing on specialty products. Wine, Christmas trees, honey, and cheese are all among the goods produced locally on successful Little Compton farms today. Walker’s has taken another route: banking on the fact that people want high quality produce, for even their simplest vegetable staples. This roadside stand, opened in 1964, sells top quality tomatoes, corn, and other Walker-grown produce whose freshness has made a name for itself all over the state. Instead of bringing the produce to the people (which Coll Walker used to do on a market truck when he started out), he has now brought the people to the produce and cemented Little Compton’s status as a farm-centric community in the modern era.

6. Simmons Mill Pond

By now, it should not come as a surprise that “in Little Compton, traditional ways prevailed long after machines began to take over on farms in other places.” This has always been a retrospective town. But one way in which the town embraced industrial promise early was the gristmill. If you walk down the path to Simmons Pond you will see the site of what was once a productive gristmill, built in 1750 by Benjamin Simmons, that made flour and meal by using water power to turn a grindstone. The photo on the right shows a formation of rocks, now so overgrown with plants as to almost hide the remains of the industrial apparatus that once operated below the dam. There were also a number of windmills in town, including a “Spider Mill” that stood on tall stilts able to pivot to catch wind from any direction. The prevalence of such machinery in the eighteenth century allowed Little Compton to grow its commercial commitment to agriculture.

Among the helpful hand painted signs describing the flora and fauna of Simmons Mill Pond, there are a number of clues as to how this land used to look. For example, a stone wall peeking through the forest’s underbrush marks an old property or pasture boundary, now disregarded by nature. Such “ghost farms” are scattered throughout the town, and provide an intimate glimpse into its history, as long as one knows how to look.

7. Tripp Farm

Above all, Little Compton’s claim to agricultural fame is the Rhode Island Red. This breed of dual-purpose hen took the region by storm in the latter half of the nineteenth century, when poultry farms exploded in both popularity and efficiency. William Tripp, whose farm was at this spot (as commemorated by the plaque on the southwest corner of the intersection) was the first to breed this chicken. Tripp introduced into his existing flock an Asian “Chittagong” that had been procured by a family member on the New Bedford whaling docks, which peddled many exotic goods. The fresh genes proved to be advantageous, and the Rhode Island Red was remarkable for its size and laying abilities. The size of Tripp’s flock increased rapidly, but it was when he sold a specimen to Isaac C. Wilbour on the other side of town that the breed’s promise truly became apparent.

Prior to the introduction of the Rhode Island Red, chickens had not been regarded as a particularly prestigious or lucrative crop, and few farms had significant commercially-sized flocks. But Wilbour noticed increased demand for eggs in nearby urban markets and scaled up his operation with the promising efficiency of the Rhode Island Red. His products were transported by steamship out of Sakonnet Point and by railroad out of Tiverton to the busy markets in Providence and Fall River. Wilbour pioneered a colony-style of hen farming in which chickens laid eggs in moveable sheds to facilitate easy pasture rotation. At its peak in the 1890s, Wilbour’s Prospect Hill Farm of over 260 acres produced 150,000 dozen eggs annually. Noting his prosperity, and persuaded by the successful marketing of the Rhode Island Red, poultry farms sprang up all across New England. Eventually, other breeds that were “developed for assembly-line production” surpassed the Rhode Island Red in popularity and efficiency. Though its dominance on local farms diminished by the mid-twentieth century, the Rhode Island Red was voted the state’s official bird and there are at least two statues commemorating it in this town.

Little Compton is clearly proud of its farming heritage—continuing to protect land for agricultural use, preserving centuries-old indicators of a productive landscape, and reimagining practices to keep up with modern times. It is this last point, noting the broad movement of American society away from household farming over the past two hundred years, that Little Compton interprets differently. Having always existed in the worlds both of secluded rurality and worldly ambition, Little Compton has maintained an uninterrupted commitment to small scale agriculture. This persists well into the twenty-first century if not for its economic opportunity, then for its associate lifestyle of Yankee values, or maybe simply its quaint appeal. I recommend visiting the Little Compton Historical Society for more information on local history. It is located on the historic farm of the Wilbour family and has an impressive collection of historic farm equipment and architecture exhibited.