New York in Newport

From a twenty-first century vantage point, the cities of Newport, Rhode Island and New York, New York may seem to be opposites in many ways. New York City is a metropolis famously on the vanguard of commercial and cultural progress—laced with innovation, obsessed with expansion, thoroughly forward-looking. Newport, on the other hand, can be seen as a quaint seaside town still relishing in its foregone heydays and reliant on an economy of nostalgic tourism. However, the two towns started from similar places and, even as they have diverged, they have maintained a unique connection. The goal of this tour is to tell a history of Newport, with New York City as the foil to track its evolution.

In the early colonial period, both towns had a more mercantile focus than many of their peer English settlements in the northeastern colonies. The typical New England town gathered around a common church but both Newport and New York were organized around their safe harbors, allowing them to grow quickly in trade. Newport was also remarkable in its commitment to diversity and creativity. This attitude was endemic to the rebellious colony of Rhode Island and chiefly so to Newport, its renegade treasure. At the time, defiant commercial ports like these two were often seen to be a cultural threat to more conservative and religious locales.

New York’s faster track to growth became most apparent after the Revolution and through the nineteenth century when industrialization fueled its massive growth in population and stratified wealth. Newport, on the other hand, was largely excluded from rapid industrialization—a reality which both hurt its prominence in trade and enabled it to embrace a different role as a refined and placid getaway. The tourist industry has deep roots in Newport and continues to buoy its economy today, though the city’s history illustrates a deep complexity to this current appearance.

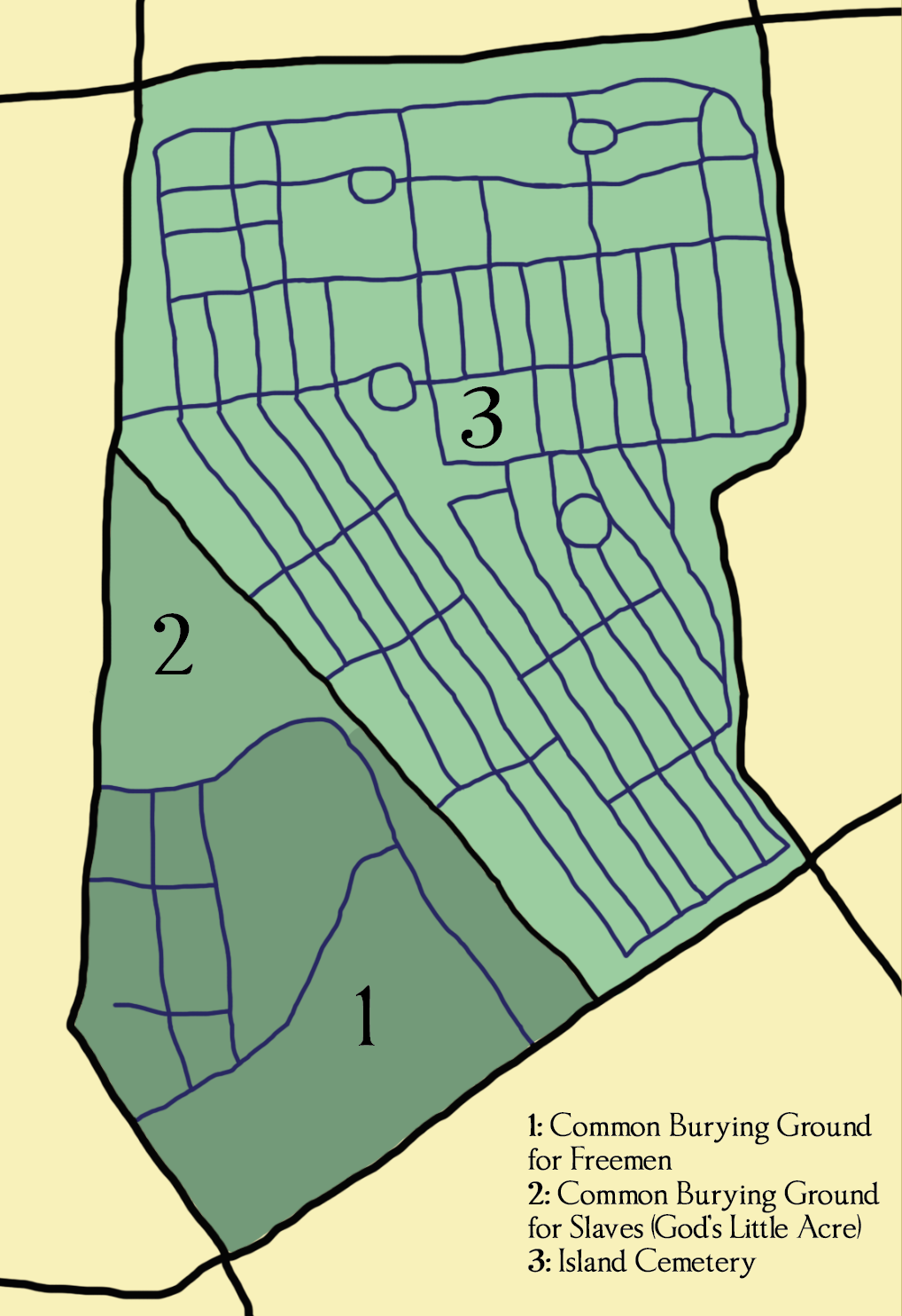

1. Common Burying Ground

Newport was founded in 1639 on the same radical principle of religious freedom that had brought Roger Williams to settle Providence three years prior. However, the town’s nine founders were not only driven by the push factor of fleeing religious oppression, but also pulled by the economic prosperity promised by new land. Newport was somewhat unlike other fledgling New England towns in that its inhabitants did not rely on subsistence farming (which brought hardship to nearly all) and collective worship (which justified the toil). Rather, early Newporters embraced a more feudal land concept that sought “to replicate the large-scale agricultural holdings so profitable back in England.” Moreover, the founders sought to construct an economy that was more mercantile than it was agrarian. These two central characteristics of Newport—its religious freedom and its commercial focus—made it a diverse town from the start.

A walk through the Common Burying Ground and Island Cemetery demonstrates the diversity of the town and its changing dynamics across several centuries. Technically these are two separate cemeteries—the first of which was established in 1640 and the second in the mid-nineteenth century. A meandering walk through the property makes familiar the names of prominent families in Newport throughout the centuries: Belmonts, Champlins, Cranstons, Coggeshalls, Eastons, Hazards, Goddards, Perrys, and Townsends are all buried here. The town’s laymen are also buried among local legends, and contribute the majority of the volume that makes up this sprawling cemetery. The Common Burying Ground alone has 3,000 headstones, 800 of which date prior to 1800.

It was not an entirely egalitarian cemetery though, with segregated sections for slaves, Jews, and Catholics, as was often customary. Nonetheless, being “a resting place for everyman and anyman,” the cemetery emphasizes its value of commonality in more than its name. This liberal notion of equality was also reflected in the state’s unique royal charter from King Charles II. Broadly speaking, the 1663 charter gave Rhode Island colonists the power to elect their own government and protected the exercise of religious freedom. What now seem like self-evident conditions of American government were at the time radical and exceptional in the British colonies. This charter gave Newport the footing to pursue freer trade and attract a relatively diverse population as it grew throughout the seventeenth century.

2. The Parade

In breaking radically from their Massachusetts progenitors, Newporters did not arrange their fledgling town around the common church green as was customary in New England settlements. This departure was to signify that not all aspects of life were to be organized and dictated by the established church. Rather, the central green of early Newport was known as the Parade (now Eisenhower Park on Washington Square). The Parade had no church framing it; in fact in the earliest days of the Newport settlement “evidence of any real church building is scant.” The radical Baptists and Quakers that made up much of Newport’s seventeenth century population generally avoided conspicuous markers of their faith (Massachusetts Congregationalists, too, spurned garish worship, the difference being that they did place their church at the center of community life for all). In Newport, religious diversity and freedom allowed the communal emphasis to be on commerce instead.

This somewhat paradoxical origin of Newport—in which religion was both central to the founding principle and not the sole focus of community life—worried many of its peers. The town’s emergence as a prominent port also welcomed an exceedingly diverse population, which gave it the reputation of cosmopolitan corruption. Historian Rockwell Stensurd writes that, “the freewheeling and rambunctious spirit later associated with America’s Wild West had found its origins in Yankee Newport.” Dr. Alexander Hamilton (no relation to the founding father) wrote in his travel Itinerarium that Newporters were “not so straight laced in religion here as in other parts of New England.” English Parliament thought of Rhode Island as a “problematic, renegade colony filled with feisty freethinkers.” James Madison wrote that “nothing can exceed the wickedness and folly which continue to rule there. All sense of character, as well as of right, is obliterated. Paper money is still their idol, though it is debased eight to one.”

Critics and conservatives said similar things of New York City in the eighteenth century, as it grew into its identity as a cosmopolitan commercial hub (see tour: New York's Capital Years). Dutch New Amsterdam was an active commercial port in an optimal trading location with both a safe harbor and river access inland. When British troops seized the city in 1664, it already had significant mercantile momentum, an emphasis which has continued to define its productive economy to this day. Newport also maintained its affiliation with money and status, earning the nicknames in later centuries of “The Island of Error” “Rogue’s Retreat.”

3. Sayer's Wharf

In the seventeenth century, Governor Samuel Cranston unified disparate Rhode Island towns, to create a colony “organized to aid the growth of Newport’s trade.” Even as it emerged as a salient port, Newport was acutely aware of its rivalry with nearby Boston—which had been implicit since the day the town's founders broke from reigning Congregationalists to seek religious freedom in the new colony. Nonetheless, by the 1720s, Newport was entering its first Golden Age, in which its shipbuilding and trade businesses boomed and lifted the town to “the ranks of being one of the five major colonial towns of the eighteenth century, along with Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston.” Even as Providence began to eclipse the town’s dominance in Rhode Island in the middle of the century as its manufacturing and industrial economy rose, Newport still remained “an entrepreneurial environment that welcomed change and rewarded ambition.” It is this spirit that allowed the town to compete with New York on matters of trade; “Toward the end of the colonial era, Newport would boast of a more robust trade, both domestic and overseas, than New York.”

As the eighteenth century progressed and the colonies grew increasingly interested in independence and wanted to defy England’s imperial trade restrictions, Newport trade started to suffer. In the absence of direct trade with Europe, the standard route that emerged out of Newport was shipping raw agricultural goods to the Caribbean in exchange for sugar which they would distill into rum onshore and then sell in West Africa in exchange for slaves. This triangular trade route was effective in cutting out Britain when their political relationship strained, but after the Revolution even trade in the West Indies was no longer viable due to embargoes placed by the British. Moving into the nineteenth century, attention and money in the new nation turned westward rather than seaward, and Newport took another blow. With the advent of the steam engine and growth of railroads, industrialization continued to bypass Newport. The first railroad bridge off of Aquidneck Island was not constructed until the 1860s. By then, changing commercial tides, as well as damage from the War of 1812 and Hurricane of 1815, had all but secured Newport’s decline as a trading hub.

The port continued to make sea ventures to Europe, China, and Africa, but most of its trade in the nineteenth century was along the Atlantic coast of North America. Packet ships became popular, shuttling passengers and goods to and from New York on a daily basis, but in the middle of the century, rail became the faster and more favorable method of transport. However, the Newport economy was resilient, as over the prior decades prosperity in shipbuilding had spurred other artisan crafts such as furniture, silver, and textile making. These traditions were woven into the fabric and culture of the town. They were dependent on creativity and cultural significance, and therefore could not be easily transferred elsewhere as a means of efficiency.

Newport’s reputation for refined goods and culture grew out of the town’s commitment to the principle that “prosperity begat creativity. Creativity begat production (works of art, books, artifacts, furniture), which, in turn, led to another level of prosperity (monetary, emotional, intellectual).” Some argue that it was the arrival of the New York Yacht Club in 1889, whose second home was originally built here at Sayer’s Wharf (now location of The Mooring restaurant), that truly “elevated the town from a merely local pleasure center to international renown.” From there, the town has continued to flourish in its upscale production and maritime recreation.

4. Trinity Church

In the seventeenth century, Rhode Island and Newport culture was made distinct by its simultaneous embrace of disparate religious beliefs. Such a culture existed in direct contrast to, and rebellion against, the established churches of England and Massachusetts, which condoned only Anglicanism and Congregationalism, respectively. The two most prominent groups that prospered in early Newport were the Baptists and the Quakers, both of whom were considered radical in the audacity of their beliefs and in the austerity of their practices. As Newport continued to grow throughout the eighteenth century, and its reputation for religious freedom attracted new Protestant denominations, many residents and congregations began to yearn for more ceremonial expressions of faith. They wanted “more learned preachers, more elegant ceremonies, more beautiful meetinghouses,” such luxuries were seldom offered by Quakers and Baptists who were keen to emphasize prudence and frugality in interpreting the word of God.

Still, Anglicanism was a perceived enemy of those committed to Rhode Island’s resistance project. However, these stewing cultural changes may have primed Newporters for its arrival in 1698 by way of Samuel Myles, a clergyman from London, as he was able to assemble a small following among the town’s diverse population. Their site of worship was a small church built in a field adjacent to where Trinity Church now stands. By the second decade of the eighteenth century, the congregation and its library had grown enough (largely due to the proselytizing of ministers John Lockyer and James Honyman) that a new building was completed in 1726. It still stands today as Trinity Church, and is a continued site of worship for the longstanding Episcopalian congregation.

It was George Berkeley’s arrival to Newport in 1729 that truly raised the profile of the Anglican Church and also of the more general English gentleman’s identity. As fortunes made in Newport continued to climb, so too did the eagerness to become, “refined, well dressed, debonair, but mostly, erudite and well-read.” Berkeley was a prominent and respected Irish philosopher and theologian who was drawn to Newport as a suitable location from which to oversee the prospective construction of a school in Bermuda funded by Parliament to advance the Anglican creed. Impressive crowds gathered at the newly completed Trinity Church to hear him preach during his three year stay in Rhode Island. His legacy lasted much longer, leaving Newport markedly more similar to London than ever before.

As revolution in the colonies grew more anticipated while the century progressed, Newport’s original commitment to rebellion superseded its recent resemblance to London. Unlike New York, another Episcopalian stronghold in the colonies, Newport did not suffer the same accusations of loyalism. While Trinity was indeed “the most dominant Episcopal congregation in all of New England at the time of the Revolution,” the town did not officially recognize one religion over another and remained remarkable in its diversity. Both New York and Newport had robust Anglican churches (to become known as Episcopal after independence) and had extended British occupations during the war, indicating to some suspected loyalist inclinations. Of course, patriotism ultimately prevailed in both places, but even after the war, Rhode Island remained skeptical of federalism, and did not send any delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. This is not to say that New York or Newport were not devoted to the cause, but rather that both cities at the time of the Revolution had religious and commercial qualities which linked their interests to England and complicated the pursuit of independence.

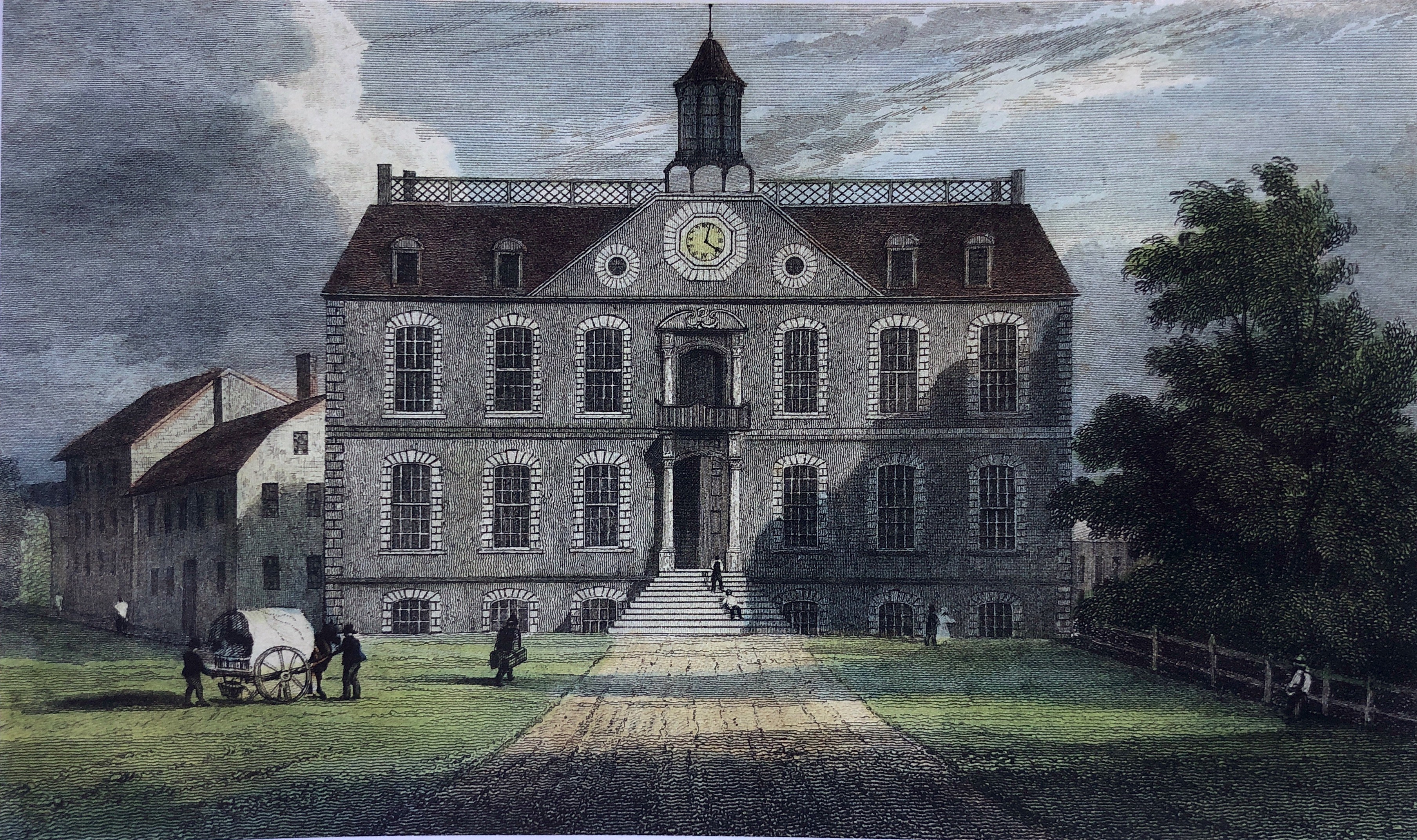

5. Bellevue House

Newport had a notable tourism industry as early as the 1750s, with its early ties being linked to plantation owners in the Southern and Caribbean colonies who wanted to escape intolerable weather and malaria in the summer. It was in the nineteenth century that tourism truly began to flouirsh in Newport, as leisure travel became accessible to the middle class for the first time.

By the 1830s, the same forces that had excluded Newport from industrial growth and caused it to decline—chiefly its geography and culture—now made it appealing as a refuge from those heavily industrialized places. One of the first hotels constructed to support this expanding tourist base was the Bellevue House, which opened in 1825 and was popular among Southerners and New Yorkers alike. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Newport had grown quite crowded in the summer. Social hotels called Ocean House and Atlantic House were two of the most significant additions to the Newport hotel scene; both have since burned down. Situated on Bellevue Avenue, they drew the town’s social arena eastward and attracted crowds at their public social events.

The coterie that summered in Newport was growing increasingly refined as New York families sought destinations for their industrial fortunes and leisure time. The New York Times began dispatching reporters to cover the social scene of Newport in the mid-nineteenth century—two excerpts can be seen below, three years apart, marking both the diversity of happenings and the evolution from the significant to the somewhat vapid. Many remarked that the swift growth and elevation of the Newport social scene made it become claustrophobic as the narrow streets could only accommodate so much commotion. After the Civil war, southerners virtually ceased coming to Newport, leaving New York high society to rise further and fill up the space. So known were the social goings-on of the Newport summer community that by the end of the century, a social life that had once thrived in relatively public hotels, transitioned to private and more exclusive homes further down Bellevue Avenue.

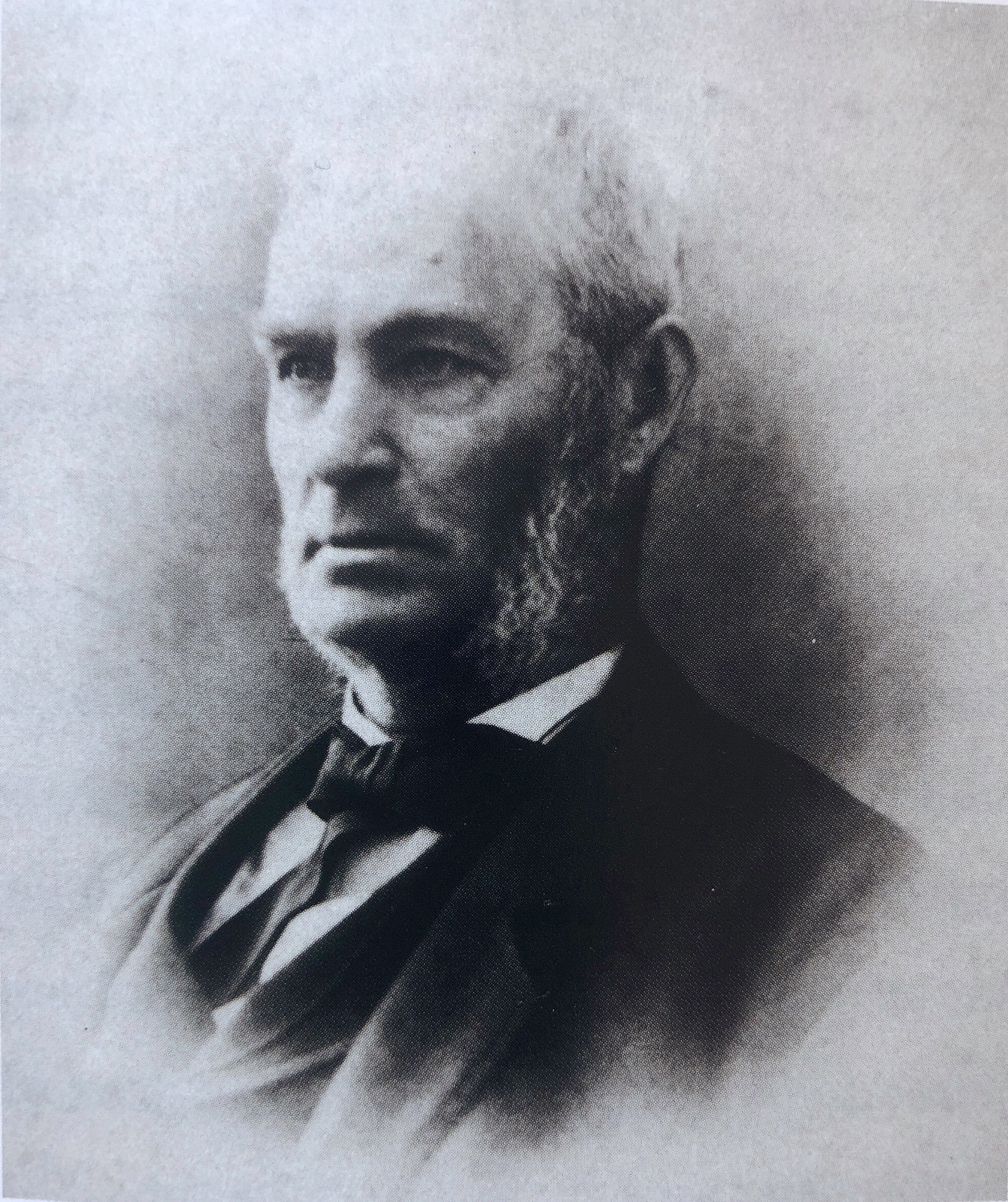

Alfred Smith

One man was chiefly responsible for facilitating the transition toward a more private summer in Newport. Historian Rockwell Stensrud writes, “Through his efforts, Newport was transformed from a tourist town dependent on hotels catering to a largely southern constituency to a summer-colony community of northern big-city tycoons building and frolicking in mansions.”

Alfred Smith was born in Middletown in 1809. He trained as a tailor which brought him to New York City, where he began working for the same kind of wealthy clients that were scouting out Newport as summer destination. Soon enough, Smith became “the fellow to consult for local information.” He returned to Newport at age 30 to get involved in the emerging land market himself. He bought 300 acres of farmland in what is now the Kay-Catherine-Old Beach Road neighborhood and began to transform the grazing pastures into a desirable real estate district. He subdivided lots, implemented a street grid, and planted rows of trees—all in effort to make the place an attractive location for budding estates.

With Smith’s enticement, the city grew eastward, away from the harbor. As his profits surged, he turned southward down Bellevue Avenue. Under Smith’s guidance, the street was extended and widened in 1852 and soon its bordering lots began to skyrocket in value. A savvy businessman, he partnered with other large landowners, notably Joseph Bailey, to develop this stretch with summer homes for the urban elite. Smith’s next project was the construction of Ocean Avenue in 1868 to connect the new edges of the city with the harbor at its heart. This physical expansion of Newport happened rapidly, and by the end of the nineteenth century, the real estate market in Newport had grown so much as to attract some of the wealthiest families in the country.

Julia Ward Howe

Most famous for penning the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” in 1862, Julia Ward Howe also cultivated the rich intellectual life of Newporters in the nineteenth century. While many of the town’s new visitors were attracted by the opportunities to flash their wealth, a group did exist, composed of writers and artists, that was more concerned with inner ponderings than outer appearances.

Julia Ward, born in 1819, descended from colonial governors of Rhode Island but was raised in New York City with all of the fixtures of modern high society. She spent many summers at her father’s house in Newport and, in 1852, she and her husband (Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe) purchased a farm of their own in Portsmouth. In 1871, she founded the Town and Country Club for those Newporters more concerned with the life of the mind than with showing off their excesses around town. She, and many others, were skeptical of what they saw as the rising superficiality of Newport summer life; she remarked that the creation of the Town and Country Club was born out of “the need of upholding the higher social ideals, and of not leaving true culture unrepresented, even in a summer watering place.” Soon enough, the Portsmouth farm “became the nerve center for intellectual and social gatherings for many years. Practically every writer or artist of note who visited Newport in the second half of the nineteenth century attended one of her social salads at the Howe house as a matter of course.” Among her most notable visitors were Mark Twain, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Singer Sargent, Edgar Allan Poe, and Oscar Wilde.

The club was not always straight-laced and high-minded—many of the meetings included satirical recitations and merriment. One magazine reported that “They meet for fun and frolic and are not harassed by fears for their good clothes or by any other trifling matters which disturb fashionable aristocrats of Bellevue when they attempt to picnic.”

Of course, the aims of the Town and Country Club were not entirely unprecedented. The group drew from the town’s long-standing intellectual and creative traditions which dated back to the colonial era when the general public was regularly involved in discussions of theology and the development of artistic craft. The enduring institution from that period is the Redwood Library on Bellevue Avenue, established 1747. To this day, it offers diverse programming and maintains an extensive written collection to continue to promote intellectual culture in the community.

6. Beechwood Mansion

These days Newport is perhaps most famous for the Gilded Age mansions that frame Bellevue Avenue. The majority of these extravagant structures are the former summer homes of New York’s most elite families. The Beechwood, for example, was the Astor family mansion, bought in 1880 by William Backhouse Astor Jr. It is not the most ornate of the Newport mansions, but it was indeed the Astors who were more influential in high society than any other family. William Astor’s wife, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, made herself known simply as “the Mrs. Astor,” and for three decades was the gatekeeper to high society in New York and, by extension, Newport.

The Astors (and the Schermerhorns) came from old money and sought to protect their status from new industrial fortunes like that of the Vanderbilts. Mrs. Astor held regular balls at which society’s most refined and desperate would mingle, flaunting their fortunes. It was, of course, a matter of social politics who would or would not get invited, and Mrs. Astor had somewhat of a public feud with Alva Vanderbilt. When the Vanderbilts did inevitably get accepted into the ranks of Mrs. Astor’s high society, the pair of women were most formidable. While the men had almost total control over the families’ finances, it was the women who were more influential players in Newport, where business was less relevant and social standing was a currency of its own.

There was a clear culture of one-upmanship prevalent in the Bellevue Avenue mansion craze. Families wanted to stand out with a villa that represented their wealth and tastes beyond what others could imagine. Though all are characterized by grandeur and opulence, there is not one common architectural movement that links the mansions. The range in appearance can be explained by a combination of somewhat fickle trends, diversity of personal tastes, and, above all, the desire to stand out. As a result, Newport has an extraordinary portfolio of stately architecture with a wide range of European influences (as well as one of the most impressive assortments of ornamental plants in the country). Among this cohort of mansion-dwellers, “the great majority were from Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue.” It is one of the Vanderbilt mansions, The Breakers, that is now perhaps the most recognizable in Newport. It is the grandest and most exhaustive in its demonstration of extravagant Gilded Age tastes.

Of course, Newport was not immune to the era’s growing distaste for the ultra-wealthy. To some, the entire collection of homes is nothing more than “a constant reminder of the plutocracy’s monuments to themselves.” Today Beechwood is one of the few mansions still in private hands; it is owned by Oracle founder and native New Yorker Larry Ellison. The mansions that are open to the public attract many seasonal visitors from across the country and are instrumental in the town’s ongoing conversation with its history.

From here, one may find interest in the Cliff Walk, a 3.5 mile scenic trail marked in red along the map above. Alternatively, to return into town, Spring Street runs north alongside Bellevue Avenue.